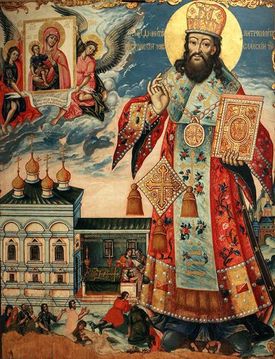

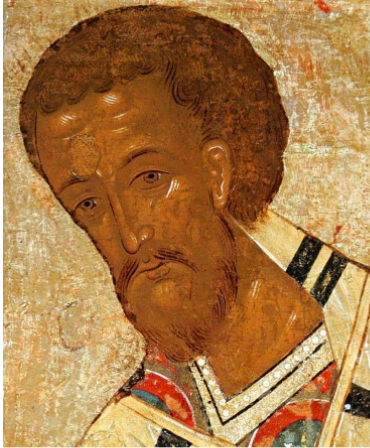

THE LIFE OF THE HOLY HIERARCH SAINT JOHN CHRYSOSTOM

BY SAINT DEMETRIUS OF ROSTOV

Saint John Chrysostom, beacon of the whole world, pillar and confirmation of the Church, and preacher of repentance, was born in the city of Antioch in Syria. His parents were unbelievers and held to the impiety of the Greeks. His father, who was an officer, was named Secundus and his mother Anthusa, and they were persons of wealth and repute.

When John reached the proper age, he was entrusted to the sophist Libanius and the philosopher Andragraphius, who instructed him in the learning of the Greeks. Although but a youth, he surpassed many older men in understanding, for he came to know the one true God, the Creator of all, and to disdain the godless polytheism of the pagans. John was baptized by the Most Holy Patriarch Meletius, who was at that time pastor of the Church of Antioch. Not long thereafter, it pleased God the most good to illumine John’s parents with the holy faith so that they who brought into the world this great luminary might not continue to wander astray in the darkness of unbelief. Secundus departed unto the Lord and a better life soon after receiving Holy Baptism, leaving Anthusa, John’s mother, a very young widow. She was little more than twenty years old when her husband died.

When John reached the age of eighteen, he went to Athens, and within a short time surpassed his fellow-students and many of the philosophers there in knowledge. He studied all the teachings and the texts of the schools there and himself became a noted philosopher and eloquent orator.

John had in Athens a malicious opponent, a philosopher named Anthimius, who was jealous of the high regard in which the saint was held. Anthimius began to slander the blessed one, but John’s wise and divinely inspired words put him to shame before all. Moreover, John led Anthimius and many others to Christ in the following manner. While Anthimius was disputing with John, he began to blaspheme our Lord Jesus Christ. Suddenly an unclean spirit gained power over him and began to torment him. Anthimius fell to the ground, beside himself, his eyes agape and foam seething from his open mouth. The onlookers were overcome by fear, and many fled. Those who remained begged John to have mercy on the possessed man and to heal him, but John replied, “If he does not repent and believe in Christ God, Whom he blasphemed, he cannot be healed.”

Anthimius straightway cried out, “I confess that there is no God either in heaven or on earth other than the God of the Christians, in Whom the wise John believes!”

When he had said this, the unclean spirit came forth, and Anthimius stood upon his own feet, restored to health. All the people who beheld this miracle cried, “Great is the God of the Christians, Who alone works wonders!”

Saint John forbade Anthimius to continue to blaspheme the Son of God and instructed him in the teachings of the true faith. Then he sent him to the Bishop of the city, who baptized Anthimius and his entire household. Many other citizens of repute came to believe in Christ as well and were baptized. The Bishop learned that it was John who had brought about the conversion of so many pagans to Christ, so he wished to ordain him and to keep him in Athens. Moreover, he hoped that John would succeed him on the hierarchal throne, for he was very old, but John learned of this and secretly departed from the city, returning to Antioch. There he resolved to forsake all the vain glory and pride of life, to take up the humble life of a monk, and to labor for God in the angelic schema. His intention was encouraged by his close friend, whose name was Basil. This man was also born in Antioch and knew John from childhood. The two shared the same teachers and loved one another greatly, being of one mind and soul. Basil, who became a monk first, advised his companion John to take up the monastic life, and John heeded his good counsel.

John wished to enter a monastery immediately and to become a monk but was held back by his mother. Learning of his intention, she pleaded with him, weeping: “My child! I did not long enjoy conjugal life with your father, for death, in accordance with God’s will, left me a widow and you an orphan. But no sorrow has succeeded in compelling me to marry a second time and to bring another man into your father’s house. I have endured the woes and fires of widowhood with God’s help because I had the joy of gazing often upon your face, which greatly resembles that of your father. I have not squandered your father’s wealth in the troubles that have befallen me as a widow, but have preserved it untouched to provide for your needs. Therefore, I beseech you, my child: do not force a second widowhood upon me, nor arouse by your departure the sorrow within me which has scarcely abated since the death of your father. Wait until my death, which I expect with each passing day. After you have buried me alongside the bones of your father, you may do as you wish. But remain with me now for a short time while I am still alive!” And thus she persuaded him not to forsake her.

At that time, Zeno, the Archbishop of Jerusalem, happened to be in Antioch, and tonsured John a reader. He remained in that rank for three years. Then John’s mother died, and after burying her, he gave away all his possessions to those who were in need, freeing his servants and bidding farewell to his relatives and friends. He went to a monastery, where he became a monk and began to labor for the Lord day and night, toiling and struggling greatly. It was there that he wrote the books On the Priesthood, On Contrition of Heart (a most profitable work), and An Epistle to the Fallen Monk Theodore.

God bestowed upon Saint John the gift of teaching and the grace of the Holy Spirit, which worked in him even as it had in the apostles. This was revealed to one of the monks living in that monastery, an ascetic named Hesychius. Venerable in years and perfect in every virtue, this Hesychius was also clairvoyant. One night, while keeping vigil and praying, he beheld in a vision two men of a magnificent appearance, clad in white garments and shining like the sun, who came down from heaven and entered the cell of the blessed John as he stood at prayer. One of them held a scroll covered with writing, and the other held keys. When John saw them, he was afraid and hastened to fall down to the ground before them. But they took him by the hands, and raising him up, said, “Take heart and have no fear.”

John asked them, “Who are you, my lords?”

They said to him, “Do not fear, 0 man of lofty desires, 0 new Daniel, in whom the Holy Spirit has deigned to make His abode, on account of your purity of heart. We have been sent to you by the great Teacher, our Saviour Jesus Christ.”

The first of the two men stretched forth his hand and gave John the scroll. As he did this he said, “Take this scroll from my hand, for I am John, who rested on the Lord’s breast at the Mystical Supper and received from Him divine revelations. The Lord shall also bestow upon you the depths of wisdom, enabling you to nourish the people with the imperishable food of the teaching of Christ. Your lips shall stop the mouths of Jews and heretics who utter blasphemies against God.”

Then the second man stretched forth his hand and gave John the keys, saying, “I am Peter, and the keys to the kingdom have been entrusted unto me. The Lord wishes to grant you the keys of the holy churches as well, so that whomsoever you shall bind may be bound and whomsoever you shall loose may be loosed.”

The blessed John again prostrated himself before the two men, and asked, “Who am I to dare to take upon myself such great and fearful tasks? I am a sinner and worse than all other men.”

But the holy apostles took the saint by the right hand, and raising him up, said, “Stand firmly, take courage, and be strong. Do what has been commanded you, and do not conceal the gift that our Lord Jesus Christ has bestowed on you. Enlighten His people and confirm them in the faith, for He shed His blood for their sake so that they might be freed from the deception of the enemy. Teach the word of God without hesitation, remembering the Lord’s saying: Fear not, little flock, for it is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom. Do not be timid: Christ our God is pleased to bring many souls to sanctification and enlightenment through you. Numerous woes will befall you for righteousness’ sake, but you must remain as firm as adamant, for thus you shall inherit the kingdom of God.”

So saying, the apostles made the sign of the Cross over John, gave him a kiss in the Lord, and departed. Such of the brethren as were tried in the virtues the blessed Hesychius told of his vision, and they were amazed and glorified God, Who has many hidden servants, unbeknown to all. But Hesychius forbade them to tell the other monks, lest John learn of the vision and depart from them, for he did not wish that they be deprived of the presence of God’s great favorite.

John did not cease to toil either for his own salvation or for that of others, laboring fervently himself and arousing others to struggle. The slothful he inspired to strive for heavenly things, to mortify their flesh, and to subject it to the spirit. Moreover, the blessed one worked numerous miracles while living the ascetic life in that monastery.

There was a wealthy and highborn citizen of Antioch who suffered greatly from pain in his head. At length his right eye fell out and was left hanging on his cheek. Although he spent much money on skilled physicians, he received no benefit from them. He then heard report of Saint John and went to the monastery where he lived. The man approached the blessed one, fell at his feet, and asked John to heal him. The saint replied, “Such afflictions as yours befall men on account of their sins and because they have little faith in Christ. But if you believe with all your soul that Christ can heal you, and cease committing the sins you have been guilty of until now, you shall behold God’s might.”

The man declared, “I believe, Father, and will do whatsoever you require of me!”

As he said this, the man laid hold of John’s garment and placed it upon his head and his diseased eye. Immediately the pain ceased and the eye returned to its socket. The man was completely healed, as though he had never been afflicted, and returned to his home, glorifying God.

Another man, one of the elders of Antioch, whose name was Archelaus, suffered from leprosy on his face, and also went to Saint John to ask healing. The saint spoke with him for a long time and then commanded him to wash his face with the water the brethren of the monastery drank. As soon as he had done this, he was cleansed of his leprosy. Without delay he forsook the world and became a monk.

There was another man named Eucius, who from childhood was unable to see with his right eye. He came to the monastery where the blessed John lived, and received the monastic tonsure. John said to this man, “May God heal you, Brother, and may He illumine the eyes both of your soul and body.”

No sooner had the saint said this than Eucius’ blind eye was opened, and he could see clearly. When the brethren realized this, they marvelled and exclaimed, “Truly John is God’s servant, and the Holy Spirit dwells in him!”

A woman named Christina, who had an issue of blood, begged her husband to take her to Saint John. Her husband set her upon an ass, accompanied her to the monastery, and left her before the gates. He then went alone to the saint and asked him to pray that his wife be healed. John said to the man, “Tell your wife to cease doing evil and to treat her servants kindly. She must understand that she is made of the same clay as they, and must begin to care for her soul. Tell her to give alms to the poor and not to neglect her prayers. Likewise, you must be abstinent and keep yourselves pure on feast days and days of fasting, and then God will grant her healing.”

The man went to relate to his wife what Saint John had said. She vowed with all fervor that she would do as John had commanded, until her last breath. Then the man returned to tell the saint of his wife’s promise.

“Go in peace,” John said to him. The man returned to his wife and found her healed, and they joyfully returned to their home, glorifying God.

There lived in that region a very fierce lion which roamed the roads, attacking men and beasts alike. Many times the people of the district gathered together and laid in wait for the lion with spears and arrows, but they never succeeded in slaying it. The beast would emerge from a grove of oak trees and attack travellers, slaying some and wounding others: hardly ever would anyone escape. Some of its victims were caught and carried back to its den alive, only to be devoured there. The people went to John and told him of this, entreating him to assist them by his prayers. He gave them a wooden cross and told them to plant it in the ground where the lion usually appeared. The people took the cross and set it up as the saint had instructed them. Several days passed, but the beast did not show itself, so the people went to the cross and found the lion lying dead there. They rejoiced that the beast had perished and that they had been delivered from danger by the power of the cross and the saint’s prayers.

John remained in the monastery for four years. Then, desiring a life of silence, he secretly departed into the desert where he found a cave, in which he remained for two years, living only for God.

After this, Saint John fell ill, enfeebled by his indescribable labors. The cold had harmed his legs, and he was no longer able to care for himself because of his infirmity. For this reason he was compelled to leave the wilderness and to return to Antioch. This occurred in accordance with God’s providence for His Church, so that the brilliant lamp would not remain hidden in a desert cave, as though beneath a bushel, but would be placed on the lampstand of the Church to illumine all. Thus John ceased to have his dwelling among wild beasts and began to live amid men and to profit not only himself but others as well.

Upon his arrival in the city of Antioch, the blessed John was received with joy by the Most Holy Patriarch Meletius, who gave him a place to live. A short time thereafter, the Patriarch ordained John to the diaconate. He remained a deacon for five years and became the adornment of the Church, both because of the virtue of his life and on account of the edifying treatises which he wrote at that time.

While John was a deacon, Saint Meletius went to Constantinople for the occasion of the appointment of Saint Gregory of Nazianzus as patriarch. There he reposed in the Lord. When John heard of the death of Patriarch Meletius, he left Antioch and returned to the monastery where he lived earlier. The monks were very glad that John had come back, and his return occasioned a spiritual celebration. The blessed one instructed them as before, and remained there for three years, leading a quiet, God-pleasing life.

One night, while Flavian occupied the throne of Antioch, an angel of the Lord appeared to the Patriarch as he stood at prayer. The angel said, “Go tomorrow to the monastery where John, the favorite of God, has his dwelling. Bring him back to the city and ordain him presbyter, for he is a chosen vessel and God will turn a multitude of people unto Himself through him.”

An angel also appeared to John at the same time. The saint was praying in his cell during the night, according to his custom when the angel came to him and commanded him to return with Flavian to the city and to accept the priesthood. The next day, the Patriarch arrived at the monastery, and the blessed John and all the monks came forth to meet him. They bowed down before him, received his blessing, and then led him to the church with fitting honor. The Patriarch served the Holy Liturgy, communed all the brethren with the divine Mysteries, and after blessing the brethren again, returned to the city with John. The monks wept inconsolably, because they did not wish that John be taken from them.

The next day John was ordained. When the Patriarch placed his hand upon John’s head, a shining white dove suddenly appeared, flying above the saint. Seeing this, the Patriarch Flavian and all those present were amazed and stood there marvelling. Word of this miracle spread throughout Antioch, the neighboring cities, and all Syria, and those who heard of it said, “What shall this man become? The glory of the Lord has overshadowed him from the very day of his ordination!”

Once he was made a presbyter, John began to care for the salvation of men’s souls with still greater zeal. The blessed one often preached without a written text to the faithful in church, causing the people of Antioch to marvel greatly and praise him. Saint John was the first to preach in such a manner in that city: before that time no one had heard anyone proclaim the Word of God without the help of a book or a prepared text. Such was the grace that poured from his lips that those listening to his sweet words always desired to hear more. Therefore, as John preached, skilled scribes wrote

down what he said. His sermons were recopied and then read at meals and in the squares of the city. Some learned his homilies by heart, like the Psalter. The eloquent orator was loved by all, and there was no one in the city who did not desire to hear him. Whenever the people learned that John was to preach, they hastened with joy to the church. Builders abandoned the construction of buildings and magistrates the trying of cases in court; merchants forsook their wares and craftsmen their handiwork and ran to hear John. They did not wish to be deprived of even one of John’s words, counting it a great loss not to hear his sweet tongue speak. Because of this, they devised numerous titles for the saint. Some called him “the lips of God and of Christ,” others “the mellifluous.”

Many times the blessed one (especially during his first years as a priest) gave sermons rich in wisdom and learning, which could not readily be understood by certain of his hearers, who were persons of little education. Once, one such woman, who was listening to the saint speak but could not understand the meaning of what he said, cried out to him, “0 spiritual teacher! I would do well to call you John of the golden mouth. The well of your teaching is deep; however, the rope of our minds is short and cannot reach its depths!”

Then many of the people began to say, “God Himself has given you this name through this woman!” And from that time until the present the whole Church has called John by the name “Chrysostom,” which means “golden-mouthed.”

In time, the holy Chrysostom came to understand that it was not profitable to address the people in a manner they could not comprehend, so he ceased employing the refinements of rhetoric. Instead, he preached simple homilies which taught moral lessons, so that even the simplest of his hearers might fully understand and benefit from his sermons.

But Saint John was mighty in deeds as well as words. Once a woman named Eudia, whose only son was ill with a fever and about to die, took her child to the saint and begged him to heal the boy. The saint took water and thrice made the sign of the Cross with it over the sick boy, sprinkling him in the name of the Holy Trinity. Immediately the fever died down, and the child arose and then prostrated himself before the saint.

The Eparch of the city of Antioch was a man blinded by the Marcionite heresy and had done much harm to the faithful. His wife fell into a grievous illness, which no doctor could cure. Day by day she became sicker, and the Eparch summoned heretics of his persuasion to his home, beseeching them to pray for the health of his wife. They did so fervently for three days and more, but without success. Then the woman confided to her husband, “I have heard that the presbyter named John, who lives with Bishop Flavian, is a true disciple of Christ and that God grants him whatsoever he asks. I entreat you to take me to him so that we may ask him to pray for my healing, for they say that he works many miracles. The Marcionites have not helped me at all, and the impiety of their faith is evident. If their faith were true, God would have hearkened to their prayer!”

The Eparch did as his wife asked and took her to the church of the Orthodox, but since he was a heretic, he did not carry her inside. Instead, he laid her before the doors and sent word, explaining to Bishop Flavian and the presbyter John why he had come and asking them to pray the Lord Jesus Christ to heal his sick wife. The Bishop came out to the woman, accompanied by John, and said, “If you renounce your heresy and unite yourselves to the Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church, Christ the Lord will heal you.”

When the couple had agreed to this, John ordered that water be brought and asked Flavian to make the sign of the Cross over it. Then, John commanded that the water be poured over the sick woman. Straightway she arose healed, as though she had never been ifi, and glorified God. Both the Eparch and his wife united themselves to the Holy Church, renouncing the Marcionite heresy. There was great joy among the faithful over the Eparch’s conversion, but the heretics were cast into confusion and became very angry with John. They began to revile him and to spread slander against him everywhere, saying that he was a sorcerer, but God quickly sealed their lying lips and brought upon them a grievous chastisement, for there was a mighty earthquake in Antioch, and the church in which the heretics assembled fell to the ground. Many people were crushed when it collapsed, but not one of the faithful was harmed. When the remaining heretics and the pagans saw this, they acknowledged Christ’s power. Destroying their temple, the heathen turned to the true God, Who was preached by Saint John.

Some time later, Nectarius, successor of Gregory Nazianzus as Patriarch of Constantinople, reposed in peace. A long search ensued for a man worthy of the patriarchal throne. Eventually the Emperor Arcadius learned of John, because the fame of his eloquence and holy life had spread everywhere. All the people of Constantinople wished to have him as successor to Nectarius, so the Emperor without delay sent an edict to Flavian, ordering him to send John to the Imperial City. When the people of Antioch learned of this, they assembled in the cathedral and prepared to oppose the imperial emissaries, for they refused to be deprived of their beloved teacher. They would not even heed the exhortations of their Patriarch concerning the matter. John himself did not wish to go to Constantinople, since he was humble and considered himself unworthy of the lofty rank of patriarch. The Emperor learned of these things, which caused him to desire to see John and to have him as Patriarch still more. Therefore, he sent the Count Asterius to take John from the people secretly and to bring him to Constantinople.

The Count succeeded in his mission, and when John drew near the Imperial City, all its inhabitants went out to meet him. The Emperor sent a multitude of nobles to greet the saint, and then himself received him with great honor in the presence of the clergy and the people. All rejoiced at the coming of this great luminary of the Church except for Patriarch Theophilus of Alexandria and those who thought as he did. Theophilus was greatly troubled, because he envied John’s fame and hated the saint. He wished to see one of his own presbyters, whose name was Isidore, made Patriarch, and did not accept the decision of the council which elected John to the throne. Nevertheless, Theophilus was compelled to submit to the council’s resolution and to consecrate John.

The blessed one was elevated to the patriarchal throne in the year 398, on the twenty-sixth day of February. The Emperor and all his princes and nobles went to receiye the blessing of the newly consecrated Patriarch, who prayed for the ruler and the people, blessing them all. The saint then gave a most edifying homily, exhorting the Emperor to adhere firmly to the Orthodox faith, to shun heretics, to attend the services of the church frequently, and to govern in a righteous and compassionate manner. “May Your Piety know,” said he, “that I shall not fail to reprove and correct you when necessary, even as the prophet Nathan did not hesitate to upbraid King David for his transgression.”

John likewise admonished all the spiritual and secular authorities and their subordinates to fulfil their duties in an honorable way. He spoke at great length, and those who heard him were filled with delight. While the saint was speaking, a demoniac who stood in the midst of the people suddenly cast himself to the ground, and an evil spirit began to shake him violently. The possessed man cried out in a terrifying voice, and all who were present in the church were overcome by fear. The blessed John commanded that the man be brought before him, and made the sign of the precious Cross over him, driving out the unclean spirit and restoring the man to health. The Emperor and the people saw this and glorified God, Who had granted them a great luminary, a physician of both souls and bodies.

The Most Holy Patriarch John assumed the administration of the Church and began to shepherd Christ’s rational flock. He zealously sought to root out evil habits from among those of every station in life but especially among the clergy, striving to do away with incontinence, envy, injustice, and other unseemly deeds. Everywhere he sowed seeds of chastity, love, justice, and mercy, and with his eloquent tongue exhorted all to repent. He had great concern for the salvation of the souls of men, and this care did not end with the inhabitants of the Imperial City but extended to the surrounding cities and other lands. He sent out tried and God-fearing members of his clergy, holy men, to preach the word of God, to confirm the people in Orthodoxy, to do away with impiety and heresy, and to guide the erring back to the path of salvation. Many of the ancient pagan temples remaining in Phoenicia were utterly destroyed at his command, demolished down to their foundations. The Celts, who were infected with the impiety of Arianism, he wisely healed and converted to Orthodoxy. To this end, he commanded the presbyters and deacons appointed to labor among them to study the Celtic language, that they might instruct the barbarians in piety in their own tongue. He likewise enlightened the Scyths who dwelt along the Danube, and the Marcionite heresy he drove from all the lands of the east. Thus did Saint John illumine the world with the light of his teaching.

The saint also had great compassion for the poor and the sick, and he saw that the hungry were fed, the naked clothed, and orphans and widows cared for at the Church’s expense. Many were the hospitals that the blessed one erected, where the ailing and strangers could lay their heads. They were given whatever they needed and had servants and physicians to watch over them. Moreover, two God-fearing priests were appointed to care for their spiritual needs.

Saint John guided the Church diligently, strengthening the good in a spirit of love and chastising the wicked. Because of this, he was loved greatly by the virtuous but hated by the evil. He was especially detested by certain of his clergymen whom he condemned for their wicked deeds and excommunicated. This made them very angry with the Patriarch and especially with his faithful servant, the deacon Serapion, a man of honorable life, who once said to the saint in the presence of all the clergy, “Master, you will not succeed in correcting these men unless you drive them off with a staff!” Many of the clergy were filed with anger when they heard this and began to speak evilly of the holy Patriarch among the people, reviling him who was worthy of all praise. Although the saint knew of their anger, he paid it no heed, and the more he was slandered, the further his fame spread, reaching even faraway countries, so that many came from distant lands to see the saint and to hear him preach.

The Metropolitan Severian was one of those who was angered by Deacon Serapion and Saint John. At first, Severian was loved by John, but when the saint learned that Severian had blasphemed Christ, he immediately drove him away. The Empress, however, took the Metropolitan’s part, and at her request, John forgave him and they were reconciled.

Although he lived in the world and held a lofty rank, John never abandoned his former monastic struggles. Whatever time was left him after he had attended to the affairs of the Church he spent alone, locked in his cell, either praying or reading sacred books. He always kept a strict fast, and his abstinence surpassed all measure. He ate only barley bread and water, slept little, and then not on a bed but standing. He never attended feasts or banquets, as he was accustomed to fasting and abstinence from his youth and could not bear even the sight of varied and rich foods, suffering as he did from an infirmity of the stomach. He completely devoted his mind to the understanding of the divine Scriptures, and especially loved the epistles of the holy Apostle Paul, whose icon he kept in his cell.

Once, while writing an exegesis on one of the epistles of Paul, Saint John thought to himself, “Who knows whether what I am writing is pleasing to God or not? Have I understood the power of this portion of the sacred Scriptures?” He began to pray God to reveal to him the truth of the matter, and soon the Lord hearkened unto His servant, granting him the following sign. One night, John was alone in his cell, writing a commentary on the Scriptures by candlelight, Proclus, his attendant, came to the door to tell the saint the request of someone in need, but before knocking, he looked through the keyhole to see whether the Patriarch was occupied. He saw that Saint John was sitting and writing and that an elder of most venerable appearance stood behind him, bent down toward the ear of the Patriarch and speaking softly to him. The man entirely resembled Saint Paul as he was depicted upon the icon which stood against the wall. Proclus was amazed, for he did not know who was speaking with the Patriarch, nor could he understand how the elder had entered the cell, since the door was locked. He waited for the man to depart, and as soon as the hour for Matins drew near, the elder disappeared. Proclus saw this for three nights in succession, and finally dared to ask the Patriarch, “Master, who is it that speaks into your ear at night?”

“No one has been with me,” answered John.

Then Proclus told him how he had seen through the keyhole an old man of venerable appearance, whispering into his ear as he wrote. Proclus also described the man’s face and clothing, and John marvelled greatly. Then Proclus glanced at the image of Saint Paul and exclaimed, “The man whom I saw resembled in every way the saint depicted upon this icon!”

John then understood that it was the holy Apostle Paul whom Proclus had seen and that his work was pleasing to the Lord. Falling to the ground, he gave thanks to God, praying with tears in his eyes for a long time. After this he devoted himself to the writing of sacred books with still greater zeal. These works he left to the Church of Christ as a precious treasure.

The great teacher of the whole world did not hesitate to denounce every injustice and to defend the oppressed, urging the Emperor and Empress alike to wrong no one and to do good works. He threatened with God’s judgment those of the nobility and high rank who seized the property of others and defrauded the poor. Therefore, since it was not only the clergy whom the saint demanded live according to the dictates of God’s law but the secular authorities as well, he also incurred their malice. As a great fire is kindled from a little spark, so did fierce anger rise up in the hearts of those who heard the saint condemn sin in a general way, since they knew that they were guilty of the sins against which he spoke. Those who hated the saint’s teachings cursed when they heard his good and wise words, mindlessly twisting their meaning. “When the Patriarch preaches in the church,” they would say, “he does not teach but condemns; he does not instruct, he insults. Rather than exhorting the Emperor and Empress, he reviles them and all the authorities.” They also said that John was lacking in mercy and failed to cover the sins of his neighbor, for the following reason.

There lived in the imperial palace a eunuch named Eutropius, who was the chief imperial chamberlain. This man was raised to the rank of patrician, and he persuaded the Emperor to enact a law forbidding anyone to flee to a church to escape the sentence of death. According to this law, if anyone should flee to a church for this reason, he was to be removed by force and executed. Now there was an ancient custom that a man who had violated civil law in any way and had been sentenced to death could flee to a church and thus escape execution just as once the Israelites were permitted to flee to the cities of refuge. Eutropius caused this custom to be abolished, which grieved Saint John Chrysostom greatly, because he considered this to be violence against the Church. In a short time, however, Eutropius himself fell into the pit which he had dug for others, and was slain by the sword which he had sharpened. The Emperor became very angry with Eutropius because the latter committed some weighty offense, and condemned his chamberlain to death. Eutropius fled to a church and hid beneath the holy table in the altar. The blessed John, greatest of zealots, then mounted the ambo from which he instructed the people, and directed a sermon of reproof against Eutropius. He said that it was fitting that the unjust and newly decreed law be tried out on him who had devised it, but John’s enemies seized upon these words and began to censure him among the people. They condemned him for lack of mercy and accused him of failing to cover over the sins of others. Little by little, they stirred up the hearts of many, arousing hostility against John. But the saint continued to seek to please God, not men, and labored to direct the Holy Church well.

During Saint John Chrysostom’s reign as Patriarch, there still remained numerous Arians in Constantinople. They were permitted to profess their faith freely and to perform their services. The blessed one considered how he might cleanse the city of the Arian heresy, and one day, when he found a convenient occasion, said to the Emperor, “Pious Emperor, if someone were to set in your crown a worthless stone, dark and dirtied, alongside the jewels imbedded in it, would you not consider that he had dishonored the entire crown?”

“Yes, that is so,” the Emperor replied.

“Thus is this Orthodox city dishonored,” continued John, “by the presence of the unbelieving Arians. Just as the dishonoring of your crown would arouse your wrath, 0 Emperor, so does the defilement of this city by the heresy of Arianism incur God’s anger. Therefore, you would do well either to return the heretics to the unity of the faith or to drive them from the city.”

When the Emperor heard this, he commanded that the leaders of the Arians be brought before him, and asked them to recite their confession of faith in the presence of the Patriarch. When they began to utter words full of impiety, and blasphemies against our Lord Jesus Christ, the Emperor commanded that they be expelled from the city.

After some time, the Arians, who had as helpers and intercessors persons of high rank serving in the imperial palace, began to return to the city on Sundays. They would form processions and go to their chief place of assembly, chanting heretical songs which blasphemed the Most Holy Trinity. When the Most Holy Patriarch John learned this, he was troubled, fearing that the common people would join in the Arians’ processions. He ordered his clergy to walk in procession through the city with lighted candles, carrying crosses and holy icons and chanting hymns glorifying the Most Holy Trinity, composed to combat the blasphemous songs of the Arians. When the processions met, considerable tumult would arise between the Orthodox and their opponents. Once a riot ensued, and several people on either side were killed, the head of the Emperor’s eunuch Bresonus, who was among the Orthodox, being split open with a stone. The Emperor learned of this and became furious with the Arians. He forbade them to form processions or to enter the city, and thus the blasphemings of this heresy finally vanished from Constantinople.

There was a general named Gainas, by origin a barbarian, who was extremely courageous in battle and enjoyed the Emperor’s favor. This man was deceived by the heresy of Arius and persistently asked the Emperor to give one of the churches of the city to the Arians. The Emperor did not know how to answer him, since he feared that Gainas, a foul-tempered and violent man, would become angry and bring about a rebellion within the Greek Empire. The Emperor told Saint John of this and received this reply: “Call for me when Gainas next petitions you for a church, and I will answer for you.”

The next day, Gainas came before the Eniperor and asked him for a church for use by the Arians, saying that this favor was due him as recompense for his labors in time of war and his bravery. The great John was summoned to the palace, and answered Gainas thus: “A pious Emperor does not take up arms against the churches of God. These are under the care of the spiritual authorities, appointed by God. If you wish to pray, enter whichever church you wish: all the churches of the city are open to you.”

“But I am of another confession,” replied Gainas. “It is for this reason that I wish to be given a church within the city. I desire that my fellow believers have a place to worship. I ask the Emperor not to disdain my request, for I have hazarded my life and suffered wounds for him, toiling greatly in the military service of the Empire.”

John then said, “You have received recompense for your labors: great honor from the Emperor, fame, rank, and gifts. It would behoove you to reflect upon what you were before and what you are now. Once you were a poor, obscure man, but now you have become wealthy and renowned. Consider how you lived before you crossed the Danube and how you live at present. You were a simple, impoverished peasant then, clad in wretched garments, happy to have bread and water on your table; but now you are a respected and famed commander, clad in the costly uniform of a general. You possess much gold and silver and countless estates, all due to the Emperor’s beneficence. Such are the rewards you have received for your labors! Be grateful, continue to serve the Greek Empire, and do not ask for divine things as recompense for mundane service.”

Put to shame by these words, Gainas fell silent. The Emperor marvelled at John’s wisdom and how he was able with a few words to stop the mouth of the tempestuous and violent barbarian. Within a year, however, Gainas forsook the Emperor’s service, and assembling a great army, marched on Constantinople. The Emperor, who had no force at hand with which to combat him, did not know what to do, and begged Saint John to go out to meet the barbarian and to calm him. Although he knew he had enraged Gainas when he told him he ought not ask for a church for the Arians, John was prepared to lay down his life for his sheep and went to the camp of the proud barbarian. And God aided His servant, for John’s eloquence calmed the man. After transforming the wolf into a lamb and reconciling him to the Emperor, the saint returned to the city.

Some time after this, in wintertime, Saint John journeyed to Asia, in order to set aright the affairs of the churches of the saints. Although his body was feeble, he could not permit the churches of God to suffer harm at the hands of wicked pastors, for many of the bishops there were stricken with avarice. These men were engaged in selling the grace of the Holy Spirit, taking money in exchange for the ordinations they performed. One such hierarch was Anthony, Metropolitan of Ephesus, whose wicked actions were reported to the Patriarch by Eusebius, the Bishop of Valentinopolis. Saint John deposed in that land numerous bishops guilty of simony. Both those who paid for their ordinations and those who ordained them he deprived of their rank, and in their places appointed others who were more worthy. When he had set in order all the affairs of the churches of Asia, he returned to Constantinople.

Thus Saint Chrysostom continued to profit the Church of God, and did not cease to upbraid and instruct sinners freely, in the hope of healing them and leading them to repentance. He was especially quick to denounce with his eloquent tongue, that sharp sword of the Word of God, the sins of avarice and greed, which were rooted in the hearts of the powerful and wealthy, for the mighty were accustomed to defraud the weak and were ever ready to take the possessions of the poor by force. Thus the rich grew to resent him, since they were censured by their consciences but were in no way willing to renounce their vices. Their hearts were hardened, and they could not endure to hear John’s words, harboring as they did much malice against him. They plotted to do him evil and began to spread false rumors about him. The Empress Eudoxia became especially angry with him, because she interpreted all that Chrysostom said in his sermons concerning the avaricious and the unjust as pertaining to her. She assumed that his words were intended to reproach or condemn her alone, as she was consumed with an insatiable passion for wealth and had taken the possessions of many by force. Whenever John spoke of avarice as the root of all evil, threatening with God’s judgment those who defrauded others, her conscience condemned her, and the Empress laid plans to remove him from the patriarchal throne.

At that time, there lived in Constantinople a man named Theodoricus, a patrician by rank, who was exceedingly wealthy. From envy of him and desire to take his riches for herself, the Empress sought reasons to make accusation against him but found none, for Theodoricus was a good and righteous man. Failing to find an opportunity to use force against him, the Empress resorted to cunning. She summoned the patrician and said to him, “You know what great demands are continually made upon the imperial treasury, how much gold is distributed to the army for the protection of the realm, and how many are fed each day from our coffers. Because of this, our funds at present are exhausted. Therefore, we beseech you to loan a portion of your wealth to the imperial treasury, and in this way you shall find favor with us. Later you will receive back what you give us.”

Theodoricus understood that the Empress did not intend to use his money for the needs of the realm but to gratify the insatiable avarice of her own heart. He went to the blessed John, told him of the designs of the Empress, and tearfully besought the saint to defend him from her. John immediately sent a letter to the Empress, meekly and kindly exhorting her to cause no offense to Theodoricus. The Patriarch’s wise words put the Empress to shame, and although she was furious with him, she did as he wished. From that moment, Theodoricus resolved to obey the exhortations of the saint concerning the giving of alms, for John counselled everyone not to lay up treasures on earth where the hands of the envious can take them away, but rather to store them in heaven where they are coveted and stolen by no one. Theodoricus feared lest his riches bring him to utter ruin, since he knew the Empress’ character and that she would neither cease to envy him nor to search for accusations to make against him until she attained her wicked desires. For these reasons, he determined to give his wealth to the King of heaven. Retaining only a small portion of his property for the support of his household, he gave all the remainder of his great possessions to one of the Church’s hospices, to be used for the sustenance of travellers, the poor, and the ill. When the Empress heard report of this, she was greatly incensed and sent a letter to the blessed John which read: “Holy Patriarch! In accordance with your counsel, I forgave the patrician Theodoricus and took nothing from him for the needs of our Empire, but you have appropriated his property for your own enrichment! Would it not have been more fitting for us to have taken this property than for you? It was in the Emperor’s service that he became rich. Why did you not emulate us? Just as we took nothing from him, so you too ought not to have taken his possessions!”

In answer, John wrote the following letter: “I believe it is no secret to Your Piety that there was nothing to prevent me from having riches, had I desired them. My parents were noble persons of influence and much wealth. It was my own decision to renounce riches. How then would I not be ashamed now to grasp for what I have forsaken and teach others to disdain? You say that I have taken Theodoricus’ possessions for my own enrichment. Know that Theodoricus has given me nothing, and had he wished to do so, I would not have accepted anything from him. He gave his wealth to Christ by offering it for the sustenance of the poor and needy, and he has done well, for Christ will reward him a hundredfold in the age to come. It is my wish that you would do as Theodoricus did and lay up your riches in heaven. Then, when your wealth fails, you will be received into the eternal mansions. But if it is your intention to take from Christ what Theodoricus has given Him, be certain that you will not offend us, but rather Christ Himself.” After reading John’s letter, the Empress grew still more impassioned, and began to consider how she might avenge herself upon the saint.

At that time, a widow named Callitropa came from Alexandria to Constantinople for the following reason. The military Governor of Alexandria, Paulicius, who held the rank of augustalus, was told by envious persons that Callitropa possessed much gold. Paulicius was very avaricious, so after bringing false accusation against the widow, he had her arrested and required her to pay him five hundred pieces of gold. Since she did not possess such a sum, she borrowed it from her neighbors, giving as surety her clothes and household vessels. With difficulty she collected the five hundred pieces of gold, handing them over to the Governor although she was guilty of nothing. At length, Paulicius was deprived of his rank and brought to Constantinople under investigation for his doings, so the widow took ship and followed him. She presented herself to the Emperor, and falling down before him, weeping and wailing, lodged complaint against Paulicius, saying that he had extorted much money from her although she had done nothing deserving of punishment. The Emperor ordered the Eparch of the city to investigate her case, to try the matter, and to give back to the widow all that Paulicius had taken from her if he was found guilty. The Eparch, however, sided with Paulicius during the trial and found him innocent, and the widow went away empty-handed.

Callitropa went next to the Empress, and prostrating herself before her, told all her misfortunes and asked her to show mercy and help her. The greedy Empress was glad to intervene in the case, hoping thereby to obtain gold for herself. She summoned Paulicius and angrily upbraided him for his theft of another’s property and offending the poor widow. She ordered that he be imprisoned until such time as he forfeited a hundred pounds of gold. Seeing that there was no escape from the hands of the Empress, Paulicius sent a servant to bring the quantity of gold the Empress demanded. He gave her the hundred pounds, but out of this the Empress gave the widow only thirty-six gold coins. She sent the woman away, keeping the rest for herself. The widow left the Empress, weeping and bemoaning the injustice she had suffered.

Then Callitropa learned that Saint John was ever ready to protect the wronged, so she hastened to, tell him everything Paulicius and the Empress had done to her. The holy John consoled the widow and then sent for Paulicius. The saint received him in the church and said to him, “We know the injustices of which you are guilty and how you have wronged the poor, taking the possessions of others by force as you have done to this widow. Do you not fear God, the father of orphans and defender of widows? We have called you here to surrender the five hundred pieces of gold which you unjustly took from her. Give her what is hers, so that she may redeem her possessions from those who lent to her and not perish with her children in utter poverty. You will then be freed of your sin and will incline God, Whom you have angered, to have mercy on you. Otherwise He will punish you for the injustice you have done.”

“Master,” replied Paulicius, “this widow has brought far greater misfortune upon me than I upon her. She lodged complaint against me to the Empress, who took one hundred pounds of gold from me! What more does she require of me? Let her go to the Empress and claim what is hers.”

“Although the Empress may have taken much gold from you,” said Saint John, “the widow still has not received what is hers; therefore she does not share in the Empress’ guilt before you. It was not only because you extorted money from this woman that God permitted the Empress to take gold from you, but because of the other sins you committed while you were still in power and because you defrauded many. Do not attempt to justify yourself by pointing to the Empress’ sins, for I tell you that you shall not leave this place until you pay back the widow the last piece of gold which you owe her. As for the thirty-six gold coins that the Empress gave her, let them serve to cover the expenses of her journey.” And John refused to let Paulicius depart from the church.

When the Empress learned of this, she sent word to John, saying, “Let Paulicius go, for I have already taken from him sufficient gold to cover his debt.”

But John replied to the messengers, “Paulicius will not be released until he has returned to the poor woman what he took from her.”

The messengers were sent a second time with orders that Paulicius be released, but the saint told them, “If the Empress wishes me to set him free, let her send the widow her five hundred gold pieces. This ought not to present any great difficulty for her, since she took much more than this from Paulicius.”

Hearing this, the Empress was furious and immediately sent two centurions with their soldiers to the church to remove Paulicius by force. But when the soldiers were about to enter the building, an angel of the Lord suddenly appeared, standing by the doors, holding a drawn sword in his hand and forbidding them entry. As soon as the soldiers saw the fearsome angel, they took fright and fled. They returned to the Empress and told her of the apparition. Troubled in spirit, she did not dare send further communications to John concerning Paulicius, who saw that he could expect no more help from the Empress. He sent word to his house that the five hundred gold coins be brought and given to the widow, after which he was released. Joyfully receiving what was hers, the woman returned to her own city.

The Empress, however, continued to resent the blessed John, and day by day the wrath and malice in her heart against God’s righteous and guileless favorite grew greater. A short time after this, the Empress sent her servants to Saint John with a message intended both to flatter and to threaten him. It read: “Cease your opposition to us, and do not interfere in matters of state, for we do not concern ourselves with the affairs of the Church but rather permit you to deal with them according to your own judgment. Cease to denounce me and to present me as an example of an evildoer when you speak in church. Until now I have regarded you as a father and have accorded you due respect, but know that if you do not correct yourself from this time forth and begin to treat me as you ought, I shall suffer you no longer.”

When John heard the Empress’ message, he was grieved, and sighing deeply, told the servants, “The Empress desires that I should be like a corpse, which sees no evil and neither hears the voices of the wronged, their weeping and sighs, nor says anything to accuse those who sin. But since I am a bishop and the care of souls has been entrusted to me, I must watch over all with a never-sleeping eye and hear the petitions of all, instructing and upbraiding those who do not wish to repent. Indeed, I know that if I do not censure iniquity and chastize transgressors, I bring about my own damnation. I fear to keep silence in the face of evil, lest the words of Hosea serve to condemn me: The priests have hid the way of the Lord. For the divine Apostle’ commands that he who sins is to be corrected before all, so that fear will be planted in the hearts of others. Thus he teaches: Preach the word, in season and out of season; reprove, rebuke, exhort with all long-suffering and doctrine. In my sermons I do not denounce the iniquitous, but iniquity. I have not spoken directly concerning anyone in particular, nor have I ridiculed anyone, nor have I made mention of the Empress’ name to reproach her. I have rather taught and continue to teach all in general to do no evil and to take care not to offend their neighbors. If the conscience of someone who has heard our words condemns him for some wicked deed, he ought not to be angry with us but with himself. Let such a person turn away from evil and do good. If the Empress is not aware that she has committed some evil or offended someone, why is she angry with me for teaching the people to turn away from all unrighteousness? She ought rather to rejoice that she has done no wrong and to be pleased that I diligently preach salvation to the people over whom she reigns. But if she is guilty of the sins which I seek to uproot from the hearts of men by my words of instruction, then let her know that it is not I who condemn her and that I have no desire to besmirch her honor. Her own works serve as her condemnation, bringing upon her soul great dishonor. Let the Empress rage if she so wishes, but I will not cease to speak the truth. It is better for me to please God than man, for if I yet pleased men, I should not be a servant of Christ.”

After the saint had said this and much else to the messengers, he dismissed them. They returned to the Empress and told her everything they had heard, but the Empress became still angrier with the blessed John and began to hate him greatly.

The Empress was not alone in her enmity toward the saint. There were many others who lived in a sinful manner and without repentance who counted themselves the enemies of the blessed one. These did not only live in the Imperial City but in faraway lands as well. Among them were Theophilus, the Patriarch of Alexandria, who from the beginning had no love for John and did not wish to consecrate him as patriarch; Acacius, the Bishop of Beroea; Severian of Geval; and Antiochus of Ptolemais. In Constantinople, his foes included two presbyters, five deacons, many members of the court, and three well-known, wealthy widows who led a defiled life: Marsa, Castricia, and Eugraphia. All these hated John, and taking counsel among themselves, devised accusations against him, to slander him among the people. First, they sent men to Antioch to discover if John had committed some foolish act during his childhood, but in searching they grew weary of searching, learning nothing useful for their purposes. Then his enemies in Constantinople began to communicate with Theophilus of Alexandria, that cunning liar, but even he could find no accusation to bring against John’s manner of life, which shone like the sun with virtue. Nevertheless, Theophilus continued to seek for a way to have John deposed, and at length his efforts, furthered by the Empress and other evil persons and still more by Satan himself, achieved success. Thus John came to be driven into exile in the following manner.

There lived in Alexandria a revered priest who was called Isidore the Hospitable because he was always ready to care for strangers. This man was everywhere renowned for his virtuous life and wise speech and had already reached old age: he was eighty years old and had been ordained presbyter by Saint Athanasius the Great, Patriarch of Alexandria. Theophilus harbored enmity against Isidore because when he wished to deprive the Alexandrian archpriest Peter of his rank and drive him from the Church (although he was guilty of no crime), Isidore defended Peter and proved that the accusation brought against him was false. After unjustly expelling Peter from the Church, Theophilus began to search for evidence that would permit him to excommunicate Isidore as well.

At that time, a widow named Theodotia gave Isidore a thousand pieces of gold so that he might purchase clothing for the paupers, orphans, and poor widows of Alexandria. While giving him the money, she begged Isidore to say nothing concerning the matter to Patriarch Theophilus, fearing that the latter might take the money and waste it on the erection of lavish buildings of stone. Isidore took the gold and did as the widow had requested, but some time later, Theophilus learned that Isidore had been given a thousand pieces of gold by Theodotia and without telling him had spent the money on the needs of the poor. Theophilus, who was extremely avaricious, became furious with Isidore, and hoping to besmirch the reputation of the righteous priest, brought against him a grave and untrue accusation of having committed an unnatural sin. Theophilus wrote out the accusation with his own hand and purchased false witnesses with gold. The untruth of their lies was established, however, and Isidore was found to be perfectly innocent. Nevertheless, Theophilus, in his boundless malice, still deprived him of the rank of presbyter and cast him out of the city with blows and dishonor, even though he was without blame. Isidore counted the abasement to which he was subjected, although innocent, as a great honor, and departed from Alexandria to live in silence at Nitria, where he had his dwelling while still young. He shut himself up in a hut there and patiently prayed for God’s help.

In those days, there lived in the monasteries of Egypt four brothers, virtuous men who feared God. They passed all their life in fasting and monastic labors and were called “The Tall Ones,” because they were of great stature. The names of these men were Dioscorus, Ammon, Eusebius, and Euthymius. They were held in esteem not only by the people of Alexandria but also by Theophilus, who revered them highly for the virtue of their lives, which was acclaimed by all. Theophilus made one of them, Dioscorus, Bishop of Hermopolis against his will and compelled two of the others, Ammon and Euthymius, to accept the priestly rank. Now the Dioscorus of whom we speak was not the heretical Patriarch of Alexandria, condemned by the holy fathers at the Fourth Council, but another, who lived a holy life and came to a blessed end. This Dioscorus lived many years before the other.

After ordaining Ammon and Euthymius, Theophilus requested that they remain with him at the patriarchal palace, during which time they saw that he did not live in a godly manner. Perceiving that he loved gold more than God and committed many injustices, they left the Patriarch’s residence and returned to their life of silence. When Theophilus learned the reason for their departure, he was greatly offended. His former love turned to hatred, and he began to plan how he might do them evil.

First, the Patriarch spread the rumor that the Tall Brothers and the deposed Isidore were adherents of the heresy of Origen and that they had led numerous monks astray. Then, without giving any reason for his order, he sent word to the bishops living nearby to drive the venerable monastics from the desert. The bishops did as the Patriarch commanded, expelling all of the honorable and God-pleasing ascetics from the hills and the wilderness. Then the exiles assembled with certain presbyters and set off for Alexandria to speak to the Patriarch. They entreated him to tell them why they had fallen into disfavor and had been driven from their dwellings, but he glared at them as though he were possessed, and casting his omophorion over Ammon’s neck, Theophilus beat him with his own hands until the holy priest was covered with blood. While doing this, the Patriarch cried out, “Curse Origen, you heretic!” Then he pommeled the others until they were covered with blood. He did not permit them to say a single word in his presence and finally, in a rage, drove them all out in dishonor. The monks returned to their huts without having received any satisfaction from the Patriarch.

Theophilus then assembled the bishops of the land and anathematized the four innocent monks, Ammon, Eusebius, and Euthymius, the brothers of Dioscorus, and the previously mentioned Isidore the Blessed, without questioning them concerning their beliefs or even summoning them to be present. But still his malice had not spent itself, so he occupied himself with writing numerous false accusations against them. He charged them with heresy, sorcery, and many other grievous sins, and then bribed slanderers and false witnesses, giving these evil men copies of the accusations he had composed. He charged his hirelings to come before him as he was teaching the people in church on a feast day, to bring forth the charges of wrongdoing against the monks, and to offer false testimony against them.

When all had been done according to his instructions, the Patriarch commanded that the libel against the monks be read publicly in the cathedral. Then he showed the accusations to the Eparch of the city, and received from him a band of five hundred Bedouin soldiers. He set off with them to Nitria with the intention of driving out of Egypt as heretics and sorcerers Isidore, the Tall Brothers, and all the monks who were their disciples. First he sent his soldiers to remove Dioscorus from his episcopal throne, and then, after they were aroused with wine, they fell upon Nitria, searching for Isidore and Dioscorus’ brothers: Ammon, Eusebius, and Euthymius. As these could not be found (for they had hidden in a deep pit), Theophilus ordered the soldiers to attack all the monks, to set fire to their dwellings, and to plunder their clothing, food, and other meager possessions. The drunken soldiers searched every cave in the desert and burned alive ten thousand holy ascetics. These things took place on the tenth of July, on which day the Holy Church commemorates the memory of these saints. The remaining monks fled, hiding wherever they could. After thus ravaging the desert, Theophilus returned to Alexandria.

The monks who survived the slaughter gathered and wept for a long time for their slain fathers and brethren. Then they dispersed, each going wherever he wished. Dioscorus and his brothers, the blessed Isidore, and many other monks, eminent wonder-workers who shone forth mightily in fasting and the other virtues, fled to Silvanus, the Patriarch of Jerusalem. But Theophilus straightway sent word to Silvanus and the bishops of Palestine, saying, “It is not right that you should accept those whom I have excommunicated and who have fled from me without my consent.”

The holy men were grieved not so much because they had suffered persecution and had been compelled to flee, but because Theophilus had excommunicated them from the Church without cause, numbering them among the heretics. Therefore, not knowing where else to turn, the exiles went to Saint John Chrysostom in Constantinople, hoping to find with him a safe refuge. They fell down before him with tears in their eyes and begged him to show them mercy. When John saw these men, fifty in number, who had grown old in the life of virtue, he took pity on them and wept for them like Joseph over his brethren. After learning why they had suffered such misfortune at the hands of Theophilus, he consoled them and gave them a place to live by the Church of Saint Anastasia. Their sustenance was provided not only by Saint Chrysostom but also by Saint Olympia the Deaconess, who furnished them with everything necessary from her own means. This deaconess, truly a saint, used her wealth to provide shelter and other necessities for the poor and strangers. She is commemorated on the twenty-fifth day of July. The monks were also holy men, and later the Church ordained that the names of a number of them be included in the calendar of saints.

One of the monks was a man named Hierax, who had lived as a hermit in the desert for many years. Once, demons appeared to him and said, “Old man, you shall live for another fifty years: how can you survive in this desert for so long?”

Perceiving the demons’ deceit, Hierax answered, “You grieve me when you say that I shall live such a short a time. I had prepared myself to remain in this desert for two hundred years.” When the demons heard this, they fled, utterly put to shame. Now this father, whom the demons were powerless to disturb, had been driven off by Theophilus of Alexandria. Another holy man expelled by the Patriarch was the presbyter Isaac, a disciple of Saint Macarius. He was chaste from his mother’s womb, for he was brought to the desert when he was only five years old and was reared there. So well versed in the divine Scriptures was he that he knew them by heart in their entirety. Indeed, all the monastics driven out by Theophilus were holy and venerable. The blessed John greatly revered them and did not forbid them to come to church although he did not wish to permit them to receive Holy Communion until he had learned the exact reasons for their excommunication and had reconciled them to Theophilus. He enjoined them not to bring to the Emperor their complaint against the Patriarch of Alexandria but promised that he would attempt to reconcile them with Theophilus by letter. John immediately wrote to Theophilus, beseeching him to allow the monks to return in peace to Egypt to live in their cells and once more be received into communion.

In addition to this, when Theophilus received John’s letter, he was told by certain liars and slanderers that John had accepted the exiled monks into communion, which was untrue. He was therefore furious with John and sent the saint a most insolent letter. John then wrote Theophilus a second letter, seeking to make peace with him and entreating him not to forbid the monks to return. Theophilus became angrier with John than with the monks, and his reply to John’s second letter was still more insulting than his answer to the first. When the monks saw that Theophilus was unwilling to be reconciled to them, they wrote a complaint to the Emperor, telling of all the misfortunes they had innocently suffered at the hands of Theophilus. The monks approached the Emperor with tears in their eyes as he was standing in church, gave him the charges against their persecutor, and begged him to hold a trial. Feeling pity for such honorable and virtuous men, the Emperor immediately sent a letter to the Eparch of Alexandria, ordering him to compel Theophilus to come for trial in Constantinople and requiring that he give an answer before Patriarch John and his bishops for his malice and be judged according to his deeds. The Emperor also wrote to Innocent, the Pope of Rome, requesting that he send bishops to the trial of Theophilus. The Pope straightway ordered bishops to prepare for the journey, and awaited word from the Emperor Arcadius that the Eastern bishops had assembled, but the Emperor did not write a second time, and for this reason the Western bishops did not come to Constantinople. Meanwhile, Theophilus bribed the Eparch of Alexandria, who allowed him to remain in Alexandria until he had sent to India to purchase all manner of fragrant perfumes and sweet spices. These Theophilus had loaded in ships to take with him to Constantinople. In addition to this, Theophilus won over to his side Saint Epiphanius, the Bishop of Cyprus. Theophilus wrote him, pretending to be filled with zeal for the defense of piety, and asked him to summon a council on the island of Cyprus to condemn the writings of Origen. Now Origen’s books were only condemned universally by the holy fathers of the Fifth Ecumenical Council, so they were not yet anathematized by the Church as a whole. Theophilus slandered John in his letter, saying that he was a heretic and had accepted Origenists into communion. Since Epiphanius was a guileless man, he believed these lies, even as it is said in the Scriptures: The guileless believeth every word. He did not perceive Theophilus’ craftiness, and being zealous for piety, he anathematized Origen’s writings at a local council held in Cyprus. Then he wrote John, exhorting him to do the same. But John made no haste in the matter and continued to devote himself to the study of the divine Scriptures, directing all his concern to teaching the people in church and bringing sinners to repentance.

Meanwhile, Theophilus prepared for the journey to Constantinople and asked the holy Epiphanius to accompany him. “We shall convoke a council against the Origenists there,” said he. Epiphanius gave his consent but departed for Constantinople before Theophilus, and arrived there first. Before he reached the Imperial City, however, the following incident occurred.

There lived in Constantinople a good, God-fearing nobleman named Theognostus. Theognostus was slandered to the Emperor by a certain envious official, a heretic, who said that the pious nobleman had cursed and reviled the Emperor, accusing Arcadius of having an insatiable lust for gold. According to the official, Theognostus had declared that the Emperor was bringing about the downfall of the government and was guilty of the unjust seizure of the property of others. For this reason, the Emperor condemned Theognostus and sent him to be imprisoned in Salonika. All his wealth and property were confiscated, save a single vineyard, which was situated outside the city. This the Emperor permitted to remain in Theognostus’ possession, for the support of his wife and children. On the way to Salonika, Theognostus fell ill from grief and died. His wife was cast into deep sorrow, both on account of her husband’s death and because of the loss of their possessions, so she went tearfully to Saint John and told him all her woes. The saint consoled her with edifying words and counselled her to lay her troubles upon God. He permitted her to receive food for herself and her children every day at the Church’s hostels for the poor and began to look for a convenient opportunity to intercede with the Emperor on behalf of the widow so that the possessions belonging to her would be returned. But the Empress’ malice prevented this, and Eudoxia brought great misfortune not only upon the widow but upon the blessed John as well.

When the time of the grape harvest drew near, all the people went out to their vineyards, and the Empress also went to see the imperial vineyards. On her way, she passed Theognostus’ vineyard and saw that it was truly beautiful. She entered it, picked some of the grapes’from the vines with her own hands, and ate them. In those days there was a law which deprived the landowner of possession should the Emperor or Empress enter his vineyard and remove grapes. After this the vineyard was to be counted as the Emperor’s, but the owner was either to be paid for it or receive another vineyard from the Emperor in exchange. In accordance with this law, the Empress ordered that Theognostus’ vineyard be numbered among those belonging to the Emperor. She did this for two reasons. On the one hand, she wished to do evil to Theognostus’ widow and her children, since she was angry with her for having gone to John and told him of her woes; and on the other, she hoped to find an excuse to drive John out of the Church. She knew that if John learned what she had done, he would not remain silent but would rise to the defense of the offended widow. From this, Eudoxia reasoned, dissension would arise, which would allow her to accomplish her purpose; and indeed, the matter ended as she hoped.

The wronged widow hastened to the blessed one, fell down before him, and weeping, explained to him how the Empress had taken the vineyard, her only means of support for her children. John immediately sent his archdeacon, Eutychius, to the Empress with a letter which he hoped would incline her to show mercy. He begged her to return the vineyard to the poor widow and reminded her of the good life of her parents and the virtues of the rulers who had preceded her, striving to awaken in her the fear of the Lord and to frighten her soul with the remembrance of the dread judgment of God, but the Empress refused to heed his admonitions, citing in her defense the harsh, ancient imperial laws. Moreover, she declared that it was she who had been offended by John, and boasted that she would no longer endure such insults. “Without knowing the laws of the Empire,” said she, “you have judged and condemned me as unrighteous. You have offended me by your insults, and I will not continue to endure your affronts very much longer.”

After reading the letter, Saint John went to the palace to see the Empress and sat down beside her. Then he began to admonish her in a gentle manner, saying to her many things he had not mentioned in his letter and beseeching her to return the vineyard to the widow. But the Empress replied, “I have already written to you, explaining the law enacted by previous emperors concerning vineyards. Let the widow either select another vineyard in place of her own or accept its price as payment.”

The saint insisted, “She does not require another vineyard nor does she seek to be paid for her own. Her request is that her vineyard be returned to her.”

“Do not attempt to oppose the laws enacted by the emperors of old, or it will not go well with you!” warned the Empress.

Said John, “Do not justify yourself by referring to ancient laws and decrees issued by pagan emperors. Nothing prevents you, as an Orthodox sovereign, from annulling an inequitable law and enacting a just one. Return the vineyard to the widow, lest I be compelled to call you a second Jezebel and you fall under a curse as she did!”

At this, the Empress became enraged, and the palace resounded with her cries. She spewed forth the venom hidden in her heart and said, “I will be revenged on you! Not only will I not return the vineyard: I shall neither pay Theognostus’ widow for it nor give her another! Furthermore, you will certainly be punished for the insults you have heaped upon me!” Then the Empress commanded that Saint John be driven from the palace by force.

After the holy Patriarch had been expelled from the palace in dishonor, he gave his archdeacon, Eutychius, the following command: “Tell the porters of the church that when the Empress comes to church, they are to shut the doors and not permit her or any of the members of her retinue to enter. Have them say that it was John who commanded that this be done!”

When the feast of the Exaltation of the Precious Cross arrived and the people had assembled in the church, the Emperor came also with his nobles and the Empress with all the members of her court. When the porters caught sight of the Empress approaching, they shut the doors of the church before her, and in accordance with the command of the Patriarch, forbade her entrance. When her servants cried out, “Open for our lady the Empress!” the porters replied, “The Patriarch has forbidden it!”

The Empress was filed with shame and anger, and exclaimed, “See, 0 people, how this stubborn man insults me! All are permitted to enter the church unhindered except for me. Shall I not take revenge on him and remove him from his throne?”

As the Empress cried out thus, one of her retainers unsheathed his sword and stretched forth his arm to strike the doors with his weapon, but immediately his arm withered and was left hanging like that of a corpse. When the Empress and her suite saw it, they grew very frightened and turned back; but the man whose arm was withered entered the church, and standing in the midst of the congregation, exclaimed, “Have mercy on me, 0 holy master, and heal my withered arm, which I dared to raise against the sacred temple! I have sinned: forgive me!”

Having learned the reason for the withering of the man’s arm, the saint ordered him to wash it in the washbasin of the a1tar and he was immediately healed. All the people who beheld this marvel gave glory to God. Moreover, these things were not unknown to the Emperor, but because he knew the evil disposition of the Empress, he kept silence. He loved Saint John greatly and gladly hearkened to his teaching. The Empress, however, devoted herself to devising a plan to be rid of John, and soon accomplished her intention.

Shortly thereafter, Saint Epiphanius, the Bishop of Cyprus, arrived in Constantinople. He came at the insistence of Theophilus and bore with him works written against Origen. After leaving the ship which had brought him, he went to the Church of the Holy Forerunner, which was about a mile from the city. There he served the Divine Liturgy and ordained a deacon although the canons forbid a bishop to ordain anyone in another hierarch’s diocese without the latter’s consent. Then he entered the city and took up his dwelling in a private home. John learned of Epiphanius’ arrival and how he had served in the Church of the Forerunner, ordaining a deacon in his diocese, but he was not offended with him because of this, for he knew that Epiphanius was a holy and guileless man. Instead, he sent messengers to him with a request that he come and stay with him in the patriarchal residence, as did other visiting bishops. Epiphanius, however, would not agree to this, nor would he meet with John, for he wished to remain in Theophilus’ favor. He replied thus to the messengers, “1 will have no communion with John unless he expels Dioscorus and his monks from the city and signs a repudiation of the works of Origen.”

Receiving this message, John sent back word to Epiphanius, saying, “It is not proper to act upon this matter hastily, before a council has been convened to consider it.”