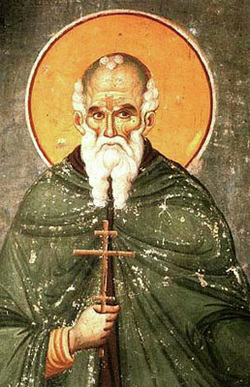

SAINT MAXIMUS THE CONFESSOR AND THE MONOTHELITE HERESY

By Dr. Vladimir Moss

The last ten years of the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius’ reign, until his death in 641, were miserable and tragic: disgraced by personal scandal and his embracing of the heresy of Monothelitism, he saw all his conquests reversed; vast areas of the East – Egypt, Syria, Palestine – were lost to the Muslim Arabs.

The Monothelite heresy embraced by Heraclius was an attempt at a compromise between the Orthodox doctrine proclaimed at Chalcedon in 451, which declared that Christ is one Person in two natures, human and Divine, and the anti-Chalcedonian heresy of the Monophysites, who taught that Christ has had only one, Divine nature since His resurrection. Since the Greek-speaking provinces of the empire were mainly Orthodox, and the Syriac- and Coptic-speaking provinces – Monophysite, the Byzantine emperors, beginning with Heraclius (610-641), had a clear political motive in trying to find a compromise theological formula. That compromise was Monothelitism; it declared that while Christ has two natures, He has only one will.

Not only did Heraclius lose the eastern provinces, but also the loyalty of most of the local populations, Semitic, Coptic and Armenian, whose religious differences with Greco-Roman Orthodoxy were compounded, according to some, by anti-Roman nationalist feeling.

However, according to Fr. John Meyendorff, “Recent research does not condone the view that Non-Chalcedonian Copts welcomed Muslims as liberators from the Roman rule: even then, and in spite of Chalcedonian persecutions, there was widespread loyalty to the Christian empire. It appears, therefore, that it is only under Persian or Arab, and later Turkish rule, when intellectual contacts with Greek theology were lost and every connection with Byzantium was viewed with suspicion by the new masters, that the Non-Chalcedonian Christians communities of the Middle East became close-knit national churches. As long as they were part of the Roman oikoumene, Syrians and Copts remained basically loyal to it ideologically, even if they had, in their majority, rejected Chalcedonian orthodoxy and suffered persecution. In their minds, their struggle was not in the name of national particularism – since neither their culture, nor their language, nor their liturgical traditions were challenged by the empire – but against that which their spiritual leaders (often Greek-speaking) saw as a betrayal of the true faith. Egypt, in particular – the cradle of the anti-Chalcedonian dissidence – was not, Peter Brown remarks, a national enclave within the Empire, but a microcosm of Mediterranean civilization, as moulded by Rome…”[1]

So the deeper reason for the political schism in the Eastern empire was not nationalism, or not primarily so, but religious. God allowed the eastern provinces to fall away from the Roman empire politically because they had already fallen away from it in faith, embracing the heresies of Monophysitism and Monothelitism. St. Anastasius of Sinai considered the defeats and defections that took place in the reign of Heraclius to be Divine punishment for his heresy…[2]

*

In this era there was a parallel between the official religion and Christology of the regime and its political theology. Thus the Orthodox doctrine of the Symphony of Powers, the cooperation of the kingship and the priesthood under the One True Faith, reflected the Chalcedonian teaching on the unity of the Divine and human natures in the one Christ. But the Monothelite emperors, who rejected the human will of Christ, and Iconoclast emperors, who likewise rejected His full incarnation, were bound also to reject the Symphony of Powers. For in accordance with their Unitarian Christologies, the emperor, instead of being a focus of unity in the religious sphere, was more naturally seen as an imposer of unity – and a false unity at that. Similarly, the Muslim rulers, who saw only one, human nature and will in Christ, believed in only one religio-political power, which necessarily made it despotic.

Thus the Monothelite heretics wanted St. Maximus the Confessor, the main champion of Chalcedonian Orthodoxy, to acknowledge the power of a Monothelite emperor over the Church, as if he were both king and priest like Melchizedek. But Maximus refused. When his interrogators asked: “What? Is not every Christian emperor a priest?” the saint replied: “No, for he has no access to the altar, and after the consecration of the bread does not elevate it with the words: ‘The holy things to the holy’. He does not baptize, he does not go on to the initiation with chrism, he does not ordain or place bishops, priests and deacons, he does not consecrate churches with oil, he does not wear the marks of the priestly dignity – the omophorion and the Gospel, as he wears those of the kingdom, the crown and the purple.” The interrogators objected: “And why does Scripture itself say that Melchizedek is ‘king and priest’ [Genesis 14.18; Hebrews 7.1]?” The saint replied: “There is only One Who is by nature King, the God of the universe, Who became for our salvation a hierarch by nature, of which Melchizedek is the unique type. If you say that there is another king and priest after the order of Melchizedek, then dare to say what comes next: ‘without father, without mother, without genealogy, of whose days there is no beginning and of whose life there is no end’ [Hebrews 7.3], and see the disastrous consequences that are entailed: such a person would be another God become man, working our salvation as a priest not in the order of Aaron, but in the order of Melchizedek. But what is the point of multiplying words? During the holy anaphora at the holy table, it is after the hierarchs and deacons and the whole order of the clergy that commemoration is made of the emperors at the same time as the laity, with the deacon saying: ‘and the deacons who have reposed in the faith, Constantine, Constans, etc.’ Equally, mention is made of the living emperors after all the clergy.”[3] And again he said: “To investigate and define dogmas of the Faith is the task not of the emperors, but of the ministers of the altar, because it is reserved to them both to anoint the emperor and to lay hands upon him, and to stand before the altar, to perform the Mystery of the Eucharist, and to perform all the other divine and most great Mysteries.”[4]

Although the main opponents of Monothelitism – St. Sophronius of Jerusalem and St. Maximus the Confessor – were Greek, four of the Eastern patriarchates fell into the heresy, leaving only the Western patriarchate of Rome to uphold the Orthodox faith. So St. Maximus fled to Carthage and then to Rome, where Pope St. Martin convened a Council in the Lateran in 649 that anathematized Monothelitism. In the second session of the Council a special libellus was composed by the eastern monks living in Rome. [5] And so, with the East sunk in heresy and overrun first by the Persians and then, more permanently, by the Muslims, the West became briefly the savior both of Orthodoxy and Romanity.

Later, Saints Martin and Maximus were arrested by Byzantine officials on the orders of the emperor, and transported in chains to Constantinople. During St. Maximus’ interrogation, when Bishop Theodosius of Caesarea claimed that the Lateran Council had been invalid since it was not convened by the Emperor, St. Maximus replied: “If only those councils are confirmed which were summoned by royal decree, then there cannot be an Orthodox Faith. Recall the councils that were summoned by royal decree against the homoousion, proclaiming the blasphemous teaching that the Son of God is not of one essence with God the Father… The Orthodox Church recognizes as true and holy only those councils at which true and infallible dogmas were established.”[6]

Saints Maximus and St. Martin suffered for the faith from the tyrant emperor Constans II, dying after torture in distant exile in the Caucasus. St. Maximus’ tongue and right hand were cut off, but by a miracle he continued to speak. He died in 666, while the truth he fought for was still trampled on. [7]

The Popes after St. Martin placed good relations with the Monothelite Eastern Empire above Orthodoxy until the death of Constans II in 668.[8] And from the time of Pope Vitalian Rome and Constantinople drew steadily closer as invasions by Arabs from the south and Lombards from the north demonstrated to the Romans how much they needed Byzantine protection. Religious differences were underplayed; Constans II received communion from the Pope on a visit to Rome; and Eastern influence in the Roman Patriarchate steadily increased.[9] Indeed, from the time of Pope St. Agatho (+680), who was a Sicilian Greek, until Pope Zacharias (+752), all the Popes were either Greeks or Syrians; the Roman Church, now filled with eastern refugees from the Muslim invasions, became a thriving centre of Byzantine faith and culture.[10]

The pattern of Greek theological leadership fortified by Western hierarchical constancy continued until the final extirpation of the heresy. Thus a local Council in Hatfield in England in 679 led by St. Theodore “the Greek”, Archbishop of Canterbury[11] anathematized Monothelitism; a local Council in Milan under Archbishop Mansuetus did the same, as did another local Council in Rome under Pope St. Agatho in 680, at which the decision of the English Council was read out by St. Wilfred of York.

This Western confession of faith was confirmed by the Eastern Churches at the Sixth Ecumenical Council at Constantinople in 681, at which St. Agatho’s epistle played an important part.

Janaury 21 / February 3, 2021.

St. Maximus the Confessor.

[1] Meyendorff, Imperial Unity and Christian Divisions, Crestwood, N.Y.: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1989, p. 27. However, Peter Mansfield writes that “Egypt was a Roman colony in the fullest sense, living under iron military government and paying exorbitant taxes” (A History of the Middle East, p. 9).

[2] Gilbert Dagron, Empereur et Prêtre (Emperor and Priest), Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1996, p. 178.

[3] Dagron, op. cit., p. 181.

[4] The Life of our Holy Father Maximus the Confessor, op. cit., p. 12.

[5] One of them may have been the future St. Theodore, Archbishop of Canterbury). He may have been the “Theodorus, abbas” who signed the decrees of the Council (Andrew Louth, Greek East and Latin West, Crestwood, N.Y.: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2007, p. 16). Cf. Andrew Ekonomou, Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes, Eastern Influences on Rome and the Papacy from Gregory the Great to Zacharias, AD 590-752, E-book, pp. 176-177.

[6] The Life of our Holy Father Maximus the Confessor, pp. 22-23.

[7] St. Maximus summed up the causes of tyranny as follows: “The greatest authors and instigators of evil are ignorance, self-love and tyranny. Each depends on the other two and is supported by them: from ignorance of God comes self-love, and from self-love comes tyranny over one’s own kind…” (Various Texts on Theology, the Divine Economy, and Virtue and Vice: First Century).

[8] Pope Vitalian seems to have cooperated in the persecution of Saints Maximus and Martin, and to have been in full communion with their persecutor, Emperor Constans II, until his death in 668, after which he preached Orthodoxy. As Louth writes, “Martin’s immediate successors – Eugenius I and Vitalian – seem to have compromised, although neither of them formally accepted the Typos, both of them were in communion with the Monothelite Patriarch Peter, who had presided at the trial of Martin. Resistance to Monothelitism was now virtually reduced to one man, the monk Maximus.” (Maximus the Confessor, pp. 17-18). See Ubipetrus, “Was Pope Vitalian a Monothelite?” Ubi Petrus Ibi Ecclesia, February 14, 2020, https://ubipetrusibiecclesia.com/2020/02/14/was-pope-vitalian-a-monothelite/?fbclid=IwAR3ujzd-yJBHUFns06WLsg-zEX79MNNJFbuZw4aNhNSSOzHy-B3lae8pz5Q

[9] An example of this was Pope Vitalian’s sending, in 668, of a Greek, St. Theodore, to be archbishop of Canterbury, and another Greek, St. Hadrian, to kick-start English ecclesiastical education, together with a Roman chanter, John, to introduce Roman Byzantine chant into England

[10] Thus the iconography of Rome in this period is unquestionably Byzantine. See Daniel Esparza, “The ‘Sistine Chapel of the Middle Ages’ is back in business”, Aleteia, May 5, 2017.

[11] St. Agatho calls him “ the archbishop and philosopher of the island of Great Britain” in his letter to the 125 bishops of the Roman Synod that was to serve as an instruction for his legates to the Sixth Ecumenical Council (http://www.intratext.com/IXT/ENG0429/_P4.HTM)

ReplyForward