SAINT MELLITUS, ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY by Dr. Vladimir Moss

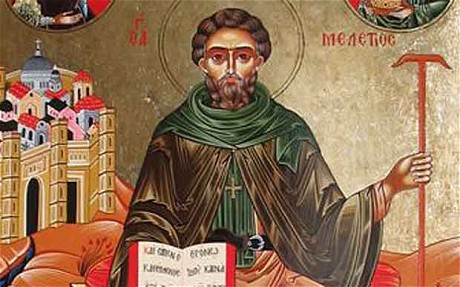

SAINT MELLITUS, ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY Our holy Father Mellitus was a Roman monk, who in 601 was sent by St. Gregory the Great, Pope of Rome, to serve as a missionary in England, helping St. Augustine of Canterbury. Having consolidated the position of the Church in Kent, Augustine set off to bring the Gospel to other parts of England. He was a very tall and strong man, and the miraculous signs that accompanied him were similarly great. Thus near York, he healed a beggar who had been suffering from blindness and paralysis; he baptized vast numbers of people in the River Swale in Yorkshire, and on leaving York he healed a leper. From Yorkshire Augustine headed for the borders of Wales, in order to meet the British bishops whose fathers had fled to the West to escape the invasions of the pagan Anglo-Saxons. Augustine had been given authority over the British bishops by St. Gregory; but the task of uniting with the British Christians did not prove to be easy. The first obstacle was that the British, having suffered much from the Anglo-Saxons, were not willing to join with Augustine in trying to convert them to the Faith. The second obstacle was that as a result of their isolation from the Church on the continent, the British Church had slipped into practices which were at variance with the apostolic traditions. One of these was that they sometimes allowed Pascha to be celebrated on the 14th day of Nisan, whereas the Council of Nicaea had decreed that it should never be celebrated before the 15th. Another was that they performed the sacrament of Baptism in an irregular manner. Augustine stipulated three conditions for union: that the British should correct these two canonical irregularities; and that they should cooperate with him in converting the Saxons. However, the British refused to accede on any of these points. At length, Augustine suggested that they pray to God to reveal His will in the following manner: “Let a sick person be brought near, and by whosoever’s prayers he will be healed, let the faith and works of that one be judged devout before God and an example for men to follow.” The British reluctantly agreed, and a blind Saxon was brought before them. The British clergy tried but failed to heal him. But through Augustine’s prayers, he received recovery of his sight. The British were impressed but pleaded for time in which to discuss these questions with their elders before coming to a decision. Augustine traveled to his second meeting with the British accompanied by Saints Mellitus and Justus. The British were represented by seven bishops and Abbot Dinoth of the great monastery of Bangor, which had over a thousand monks. Before the meeting, they had approached a hermit and asked him how they should answer Augustine. He said that if Augustine rose when they entered, this showed that he was humble and should be obeyed. If he did not rise, then they should not accede to him. Therefore when Augustine did not rise at their entrance, the British became angry and refused both to accept his stipulations and to acknowledge him as their archbishop. As the meeting broke up, St. Augustine prophesied that since the British had refused to cooperate in the conversion of the pagan English they would themselves be put to sword by the same English – a prophecy which was fulfilled a few years later when the pagan King Ethelfrid of Northumbria defeated the British in battle at Chester and killed 1200 of the monks of Bangor. On his return to the East, Augustine baptized King Sebert of Essex and consecrated St. Mellitus as bishop of Sebert’s capital, London. In the same year, he consecrated St. Justus as Bishop of Rochester. Then just before his death, he consecrated St. Laurence as his successor at Canterbury. These consecrations by a single bishop were blessed by St. Gregory as an exception to the apostolic rule that bishops should be consecrated by no less than two bishops, because of the fact that there were no other canonical bishops in Britain. St. Augustine reposed in the Lord on May 26, 605, and was buried next to the unfinished church of Saints Peter and Paul. He was succeeded by St. Laurence, who assumed the supervision of the English Church and wrote, with his fellow bishops Mellitus and Justus, to the Celtic Christians in Ireland, exhorting them to unity. But to no avail. Moreover, after the death of King Ethelbert in 616, Laurence had to face a revival of idolatry in Kent under Ethelbert’s son, Eadbald. To make things worse, King Sebert of Essex also died, and his three sons, who were pagans, allowed the people to return to idolatry. Once, while St. Mellitus was celebrating the Liturgy, they came into the church and asked the bishop: “Why do you not give to us that which bread which you used to give to our father Saba (for so they used to call him), and which you still continue to give to the people in the church?” Mellitus replied: “If you will be washed in the laver of salvation, in which your father was washed, you may also partake of the holy bread of which he partook; but if you despise the laver of salvation, you may not receive the bread of life.” They replied: “We will not enter into that laver, because we do not know that we stand in need of it, and yet we will eat of that bread.” Eventually, after a further refusal, they became angry and forced Mellitus to leave London. He then decided to go to France with St. Justus until the storm passed over. St. Laurence was also about to flee with them. But that night, the holy Apostle Peter appeared to him, and after scourging him for a long time said: “Why would you forsake the flock which has been committed to you? To what shepherds will you commit Christ’s sheep who are in the midst of wolves? Have you forgotten my example, who for the sake of those little ones whom Christ recommended to me in token of His love, underwent at the hands of infidels and enemies of Christ, bonds, stripes, imprisonment, afflictions, and lastly, the death of the cross, that I might, at last, be crowned with Him?” The next morning, St. Laurence went to King Eadbald and, taking off his garment, showed him the scars of the stripes he had received from the Apostle. The king was astonished and asked who had presumed to give such stripes to such a great man. On hearing the truth, he was terrified, abandoned both his paganism and his unlawful marriage, and was baptized. Then Laurence went to France and brought Mellitus and Justus back with him. Justus was restored to his see at Rochester, but Mellitus was not able to resume control of his see in London because of the strength of the pagan reaction. Goscelin relates of St. Laurence that he performed many miracles; he raised the dead, walked on the sea, caused a fountain to spring up in a dry place, and after the manner of the Prophet Elijah brought down fire from heaven to consume the impious. Once, after building and consecrating a church in Scotland (perhaps a men’s monastery?), he ordered that no woman should enter it. And when, in the late eleventh century, Queen Margaret of Scotland ventured to enter it, she was repulsed by some invisible force. St. Laurence reposed on February 2, 619, and was buried in the church of Saints Peter and Paul. He was succeeded in the archbishopric by St. Mellitus. As we have seen, Mellitus was bishop of London before he succeeded to the archbishopric. And it was he who, at King Sebert’s request, came to consecrate the first church at Westminster on the isle of Thorney, which is now the first church of the English capital, to God and the Apostle Peter. The night before the consecration, according to the tradition related by the Monk Sulcard, while everyone was sleeping, the Apostle Peter appeared on the bank of the Thames and motioned to a fisherman to row him over to the island. After alighting on the island, as the fisherman watched, the apostle created two streams by striking the ground with his staff and then proceeded to the newly built church to the accompaniment of the melodious voices of angels. Then the astonished spectator saw the heavens opened and the whole island bathed in a heavenly light as heaven and earth joined in magnificent service. Much as he wanted to depart, he was unable to, rooted as he was to the spot by the apostle’s chains. And after the service, Peter came back to the trembling fisherman and said: “Do not be afraid because of what you have seen and heard, for this is the will of God”. Then he explained that he was the Apostle Peter, to whom this church was being dedicated, and that he should relate what he had seen and heard to St. Mellitus. When the bishop would come he would see that the walls had already been sealed with holy chrism, so he would not have to consecrate it. And the fisherman, whose name was Edric, was to present to Mellitus one of a miraculous catch of fish which he would obtain through the apostle’s prayers, as a witness to the truth of his words. Everything turned out as the apostle said. The fishermen immediately cast his nets into the water of the river and pulled in a huge catch of salmon. And St. Mellitus, coming into the church the next day, found the signs of the heavenly consecration already on the walls. St. Mellitus suffered greatly from gout, but this did not dampen his zeal in the service of God. Once a great fire had already consumed a large part of Canterbury, and no human means seemed able to stop it. The bishop then ordered that he be carried to the church of the four martyrs, which was in the area where the fire raged most; and after his prayer, the wind suddenly changed from the south to the north, and the city was saved. St. Mellitus reposed after five years as archbishop of Canterbury, on April 24, 624. Holy Father Mellitus, pray to God for us!