ST. ANTHONY OF THE KIEV CAVES

ST. ANTHONY OF THE KIEV CAVES

Commemorated July 10/23, September 2/15, September 28/October 11

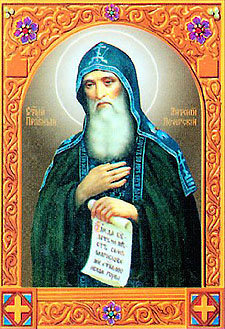

After the seeds of Divine grace had been planted through the Mystery of Baptism, it was the early growth of a native monasticism with its intense cultivation of spiritual life which most effectively encouraged the Gospel teaching to take root among the peoples of Rus’. The first of these native monasteries, the Kiev Caves Lavra, has been called “the cradle of Russian Christianity,” and its founders, Sts. Anthony and Theodosius, are appropriately venerated as the fathers of Russian monasticism. Together with their disciples, they shone forth upon the Russian land as spiritual luminaries, dispelling the darkness of paganism and calling people, by example, into Christ’s marvelous light.

* * *

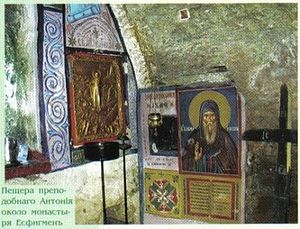

St. Anthony’s cave at EsphigmenouAt the time of the Baptism of Rus’ in 988, there lived in the town of Liubech a young boy by the name of Antip. He was educated by his parents in Christian piety, and upon coming of age he set out for the Holy Mountain of Athos to observe for himself the life of the monks whose ascetic struggles were extolled by Greek missionaries at work among the peoples of the Kievan princedom. Inspired by the monastic ideal, the youth chose to follow this angelic path himself and was soon tonsured with the name Anthony. He settled not far from the monastery of Esphigmenou in a small cave overlooking the sea.

The zealous young ascetic had been there only a few years when the abbot, prompted by Divine revelation, sent him back to his native land in order that his example might serve to draw others from among the recently enlightened people to embrace the monastic life.

Arriving in Kiev, Anthony made the rounds of the various Greek monasteries there, but finding none of them to his liking—for he was accustomed to the more austere Athonite tradition—he discovered a small cave not far from the city and there resumed his life of solitary struggle.

His peace, however, was interrupted by the fratricidal turmoil which followed upon the death of Great Prince Vladimir in 1015 and the seizure of the throne by his ruthlessly ambitious son Svyatopolk, and Anthony decided to return to Athos. But as soon as this time of troubles passed, the abbot sent him back once again to Kiev with the blessing of the Holy Mountain, encouraging him with the prophecy that many monks would join him.

On his return, Anthony discovered another cave where the ascetic priest Hilarion had been wont to retire for prayer before his appointment as first Metropolitan of Rus’. Enlarging it just enough to make it habitable, Anthony settled there as a hermit. Some kind people, on learning of his presence there, supplied him with the scant provisions he would accept. He subsisted almost exclusively on bread and water.

The saint’s life of solitude was short-lived, as people began coming to ask his blessing and counsel. Soon, there came also those who desired to share his way of life. One of the first to join the saint was the priest Nikon (March 23) who later tonsured another newcomer and Anthony’s closest disciple, Theodosius.

From the beginning, the emerging monastic community enjoyed the favor of the royal household, although it was not always a smooth relationship. When the son of a wealthy boyar gave up his worldly goods for a monastic life of voluntary poverty, his father complained to the prince. Soon thereafter a favorite among the prince’s retinue followed suit and was likewise tonsured by Nikon. Prince Izyaslav angrily demanded that Nikon persuade the two to abandon their new way of life, threatening Nikon with his wrath. “Do with me as you will,” replied Nikon calmly, “but I cannot take soldiers away from the King of Heaven.” The prince’s anger unabated, St. Anthony decided it would be expedient for him to depart for a season which he did until the prince, assuaged by his wife, the pious Maria Casimirovna, requested his return.

When the number of brothers reached twelve, Anthony expressed his desire to retire into solitude. “God has gathered you and there rests upon you His blessing and the blessing of the Holy Mountain. Now live in peace; I am appointing for you an abbot, for I wish to live alone as before.” And he began digging for himself a new cave, some two hundred yards from the old one, which later came to be known as the “Far Caves.”

The first abbot, Barlaam (Nov. 14), was soon called by Prince Izyaslav to head the monastery of St. Demetrios which he had newly established at the gates to the city. When the brethren asked St. Anthony to designate a new abbot, the choice fell upon Theodosius whom he particularly loved for his meekness and obedience.

As more new brethren joined the community and conditions became crowded, Anthony requested from the prince the hill in which the caves were located. When this was granted, the monks built there a wooden church and some cells, and encircled the area with a fence.

But even with Theodosius as abbot, St. Anthony continued to guide the community. In his humility Theodosius did nothing without going first to St. Anthony’s cave to ask his advice and his blessing. And others came, for St. Anthony was widely recognized as a holy man rich with the gifts of healing, of clairvoyance and spiritual discernment.

Once, as Prince Izyaslav and his brothers were preparing to fight the Kumans, they came to ask Anthony’s blessing. The saint foretold that because of their sins they would suffer defeat, but that the Viking prince Shimon, who had taken refuge with the princes of Rus’ after having been expelled from his native Scandinavia, would survive and return to Kiev where he would live for many more years, “and you will be buried in a church that you will build.” Both these prophecies were precisely fulfilled.

It was not long after this ill-fated campaign that Kiev became the stage of a rebellion which forced Izyaslav into exile. He suspected Anthony of sympathizing with his opposition and intended, on his return, to banish him. But before he could act on this design, his brother Svyatoslav, Prince of Chernigov, arranged for the saint to be brought secretly to Chernigov. There St. Anthony dug for himself a cave, and thus laid the foundation, as it were, of the Yeletsk Monastery which was later established on that site.

Finally Izyaslav was persuaded of the saint’ s innocence and asked that he return to Kiev. Shortly thereafter Izyaslav’s reign came to an end; he was overthrown by his brothers and Svyatoslav became Grand Prince.

In view of the steadily increasing number of monks, Sts. Anthony and Theodosius purposed to build a large stone church. Certain miraculous signs confirmed God’s blessing upon this undertaking. Many people saw a bright light at night over the proposed site of the new church, and when the Viking Prince Shimon returned from fighting the Kumans, he related that as he lay wounded on the field of battle, he saw a vision of a magnificent church set in the midst of the Caves Lavra. He had had a similar vision before setting sail from his native land. He was praying before an image of the Crucified Lord when the Saviour Himself appeared and told him that in that far away land which would receive him, a church would be built. He instructed Shimon to take from the crucifix the gold crown and gold belt with which it was adorned; the crown was to be hung above the altar of the new church, and the belt was to be used in fixing the dimensions of its foundation—thirty times its measurement in length and twenty times in breadth. As he sailed away, Shimon saw in the night sky a church set in a blaze of light. St. Anthony reverently accepted the gold crown and belt, and the church was built according to the measurements so wondrously revealed to the Viking prince.

The venerable Anthony, however, did not live to see the church completed. In 1073, soon after blessing its foundation, he peacefully gave his soul to God, having spent ninety years on this earth in fruitful spiritual labors. Before his departure he called his monks together and comforted them with the promise that he would always remain with them in spirit and would pray the Lord to bless and protect the community. He also promised that all those who stayed in the monastery in repentance and obedience to the abbot would find salvation. The saint asked that his remains be forever hidden from the eyes of men. His desire was fulfilled. He is said to have been buried in the cave where he reposed, but his relics have never been found. However, multitudes came to pray in his cave, and there, many who were sick found healing.

True to their promise, the holy founders of the Caves Monastery continued to watch over its existence even after their repose. There is, for example, the story written by Bishop Simon (+1226), a former monk of that monastery and principal author of the Kiev Caves Patericorn of how the stone church was completed.

Sts. Anthony and Theodosius had been gone from this world some ten years when a group of Greek iconographers came to the Caves Lavra demanding to see the two monks who had hired them to adorn the new church with frescoes. They were rather angry inasmuch as the church standing before them was considerably larger than they had been led to believe and would consequently require more work than was covered by the sum of gold they had received there in Constantinople upon signing the agreement. Abbot Nikon, confessing his ignorance of the matter, asked who it was that had hired them. “Their names were Anthony and Theodosius,” “Truly,” said the abbot, “I cannot summon them, for they departed this life ten years ago. But as you yourselves testify, they continue to care for this monastery even now.”

The Greeks, scarcely believing this possible, called some merchants traveling with them, who had been present at the signing of the agreement, and asked that they be shown an image of the deceased. When this was done the Greeks bowed low, for they recognized in the saints the exact likeness of the two men who had commissioned them to paint the frescoes and given them the gold. Acknowledging the supernatural power of the saints, they decided not to cancel the agreement after all and set about with heightened inspiration to embellish the church. The iconographers never returned to Constantinople; they became monks and ended their days there in the Caves Monastery.

The Dormition Church, rebuilt in 1470, was destroyed in 1941 by an explosion which the Soviets attribute to the Germans. Witnesses, however, state that it was the communists themselves who set delayed-action explosives just before the German occupation of the city.

Originally published in Orthodox America Vol. 3, no. 78, March 1988