“I Will Not Tell Thy Secret to Thine Enemies”

THE CATACOMB CHURCH IN THE SOVIET UNION by Ivan Andreyev

The All-Russian Church Council in Moscow in 1917-1918 gave the Russian Orthodox Church a firm canonical basis for the life of the Christian Church in an anti-Christian state.

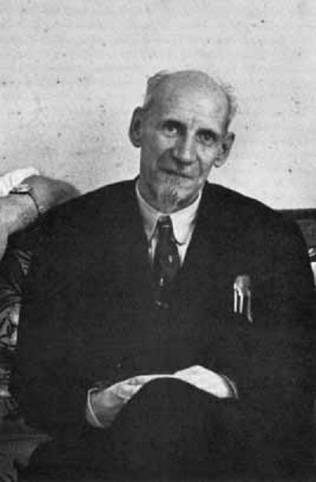

Patriarch Tikhon anathematized (19 January, 1918) the Soviet Government while the ideology-minded State whose aim was the reconstruction of the whole life of Russia on an atheistic and materialistic basis was still in statu nascendi (in a state of being born). This anathema was confirmed by the All-Russian Church Council (28 I. 1918).

While acknowledging in principle the impossibility and undesirability of a separation of Church and State, nevertheless Patriarch Tikhon and the Council, by their anathema, separated the Russian Orthodox Church from the new godless anti-Christian Soviet State. By anathematizing only this form of civil government, the Patriarch and the Council established the fact of the incompatibility of the power of the true Christian Church with the power of the spirit of anti-Christ.

A similar act also asserting the incompatibility of the Church and the State was the decree of January 23, 1918, “On Freedom of Conscience,” which was called by the All-Russian Church Council, “The Decree on Freedom from Conscience.” In the list of 1918 (No. 18, p. 203), the same decree is entitled “On the Separation of Church and State and of Church and Education.”

This separation of the State from the Church was not a mere setting of limits between the power of the State and that of the Church but a camouflaged ban that the Soviet Government laid on the Church, which by the very nature of her spirit was anti-soviet. A mutual ban, a mutual proscription of foreign, hostile, incompatible principles – the principles of the atheistic, materialistic, antichristian State with those of the militant Orthodox Christian Church – all this is quite natural.

The Soviet State and the Orthodox Church were in point of fact two utterly incompatible organizations. A struggle was inevitable and the nature of the struggle was clear. The antichristian, godless, materialistic ideology necessitated definite methods of struggle: in the first place, falsehood, then deception, propaganda, calumny, terrorization, violence, persecution, inquisition; and finally, the entire liquidation not only of the Church but even of all religion in the souls of men. In turn, the Russian Orthodox Church dictated diametrically opposite methods of combat: firstly, confession of faith and truth, exposure of scandals and deception, courageous defense of the Faith, self-denying, preaching, readiness to confess the Faith even to martyrdom; in a word, the defense, even to death, of Christ and of His Immaculate Bride, the Church.

The essence and basis of the Communist ideology showed itself at once in this struggle to be fanatically religious. It is possible to believe in the existence of God and Satan, or not, but it is impossible to deny the existence of ideas connected with these conceptions. Communist ideology is definitely and cynically associated with the idea of the denial of God and His Truth and is committed to hatred for them and war with them; in other words, it is connected with the idea of Satan.

So from the very beginning of the clash of the Church with the State in the Soviet Union, the Church stood for the service of Christ and the State for the service of Satan and antichrist. A life-and-death struggle had begun. Every Orthodox Christian was faced with a dilemma: to accept martyrdom or to compromise his conscience. To choose martyrdom one had to be a saint because the cruelty of the tortures to which the Soviet government subjected her enemies surpassed all the tortures and violence previously known in the history of mankind. By intensifying the tortures the Soviet State simultaneously intensified her insistence on spiritual enslavement.

In his remarkable pamphlet “The Church in the Soviet Union” (Paris, 1947). S. P. accurately and vividly describes the intolerable plight of the Russian people: “To put it briefly, there was and still is an opinion, simple and unequivocal: heroism and martyrdom or slavery and cooperation. The masses of the Russian people understood that in the very beginning and tried to escape by masquerading. Now the whole political development of the revolution may be described as systematic pressure on this masquerading, while on the other hand, the masqueraders are still inventing new ways of escaping notice and of avoiding pressure; new means of camouflaging their lives, new formulas of neutrality and semi-loyalty, new subterfuges, new “woods,” “ravines,” “tundra’s” where they might save themselves. It is understandable that even the practicing members of the Orthodox Church could not evade that dilemma, that masquerading.”

Just as every single individual believer had to solve this tragic dilemma for himself alone, or at most for his family and friends, so the Head of the Orthodox Church had to solve it for the whole Church. There is plenty of documentary evidence to show that often the lives of many people and sometimes the kind of tortures inflicted on them depended on a single word of the Patriarch.

In order to alleviate the unbearable suffering of the clergy and laity persecuted by the godless authorities, Patriarch Tikhon made a series of concessions and compromises. But the Soviet government was not satisfied with these concessions and demanded the full spiritual subjection of the Church to the State and intensified the persecutions. At the sight of these cruel persecutions which were becoming more and more outrageous and the moral and physical tests and tortures that were systematically exterminating the clergy and the faithful, and seeing how even “the elect” were falling and apostatizing, Patriarch Tikhon devoted all the powers of his mind and heart to the alleviation of the fate of his flock. He made such further concessions to the godless government as were possible to the religious conscience of an Orthodox Christian. But there was a limit that he never exceeded; he did not surrender the spiritual freedom of the Church to the servants of Satan.

Patriarch Tikhon was the greatest martyr of that period. He was indeed a martyr crucified in spirit. His heart was torn by the moral sufferings and the fate of Russian Orthodoxy from whom the Soviet government was demanding treason to Christ, and he was heartbroken by the plight of his flock whose sufferings were exceeding all bounds.

The diabolical lie of the government, first of all, consisted in the fact that religious persecutions were called a political struggle, while confession of faith and truth was dubbed political crime. It was in vain that the Patriarch publicly declared that he prohibited the faithful from participating in any kind of political activity; in vain that he “repented” of his “political” crimes and declared that he was “no (political) enemy” of the Soviet government. The Soviet authorities regarded even every purely religious opposition of the faithful as political opposition.

Patriarch Tikhon had the terrible conviction that the limit of the “political” demands of the Soviet government went beyond the limits of fidelity to Christ and the Church. The “masquerade” of strict adherence to the canons which had helped in the struggle with the “Renewed Schismatics” had been discovered by the Soviet authorities. Seeing that the canons were like a wall on which all violence and terror against the faithful were breaking, the Soviet authorities decided to subordinate the Church spiritually on the condition of the strictest adherence to the canonical regulations. To that end the Communists began tempting, terrorizing, and torturing not the renegades who are always ready to flout the holy canons but those who were faithful to them. This task proved extremely difficult. Those who were prepared to cooperate with the godless government were breakers of the canons, whereas those who refused to betray the canons refused also to betray the Spirit of Christ. The Soviet government needed a new Judas among the strictly canonical bishops.

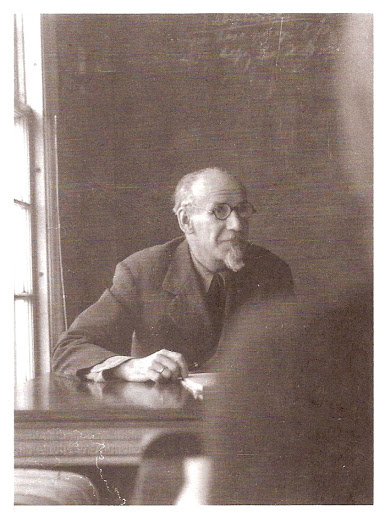

According to an intimate friend of Patriarch Tikhon, Professor M. A. Jijilenko, who was head-physician at Taganka Prison in Moscow, and who was later the first secret bishop of a catacomb church – Bishop Maxim of Serpukhov – shortly before his death, the Patriarch expressed the opinion that the only way for the Russian Orthodox Church to maintain her fidelity to Christ in the future would be to escape into the catacombs. Therefore, Patriarch Tikhon gave his blessing to Professor Jijilenko to become a secret monk. Later, if a supreme hierarch of the Church were to betray Christ and cede the spiritual freedom of the Church to the Soviet government, he was to become a secret bishop.

Patriarch Tikhon died on 25, March 1925. According to Bishop Maxim, he was poisoned. The “Will” that was found after the death of the Patriarch was unquestionably forged. It was a counterfeit produced by the Soviet government, but it did not help. So, then, with the aid of E. A. Tuchkov, that bloody executioner of the Russian Orthodox Church, a deeply conceived and diabolically cunning Declaration was composed which the Soviet authorities decided to issue in the name of the supreme hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, this hierarch being ostensibly quite canonical and authentic. This declaration was supposed to convert the Russian Orthodox Church into a Soviet church, canonically quite correct, but serving the satanic antichristian plans of the Soviet State.

Patriarch Tikhon, in his time, had categorically refused to sign a similar declaration. After the death of the Patriarch, Metropolitan Peter also refused to sign a declaration of that kind. For that he was arrested in December 1925, deported and tortured in exile; he died eleven years later. After the arrest of Metropolitan Peter, Metropolitan Sergius Starogorodsky succeeded him. Metropolitan Peter had not only refused to act as the locum tenens of the Patriarch but asked that in the event of his death being known he should be remembered in the church services as the Head of the Russian Orthodox Church – as a symbol of unity and fidelity to that Church. The martyr bishop Damaskin was witness to that. According to his own words, he actually had in his hands this last order of the locum tenens.

Metropolitan Cyril, the senior hierarch and the first candidate actually designated to the position of locum tenens by Patriarch Tikhon, also refused to sign the “Tuchkov Declaration.” Father Elias Pirozhenko and Father P. Novosiltsev, who visited him in his exile, wrote: “He told us how all that had been carried out by Metropolitan Sergius Starogorodsky had been offered to him and that he was glad to have remained on the straightway.” Metropolitan Cyril died in exile in 1936, the year of Metropolitan Peter’s death.

Similar offers to sign a declaration had been made to Metropolitan Agafangel, Metropolitan Joseph, and Archbishop Seraphim of Uglitch, that is, to all the most outstanding hierarchs from the spiritual point of view and the greatest sticklers for canonical integrity. At last, a Judas was found among the bishops who was canonically correct. True, in the gravest moment in the history of the Russian Church, when the “Renewers” began to triumph, he went over to them; but afterwards he did penance in a canonically correct manner. This was Metropolitan Sergius. He delivered the Russian Orthodox Church into the hands of the enemies of Christ, but he gave his treachery a strictly canonical form. He signed the Tuchkov Declaration and polished its formulation. The Declaration was issued in the name of the representative of the Locum Tenens of the Patriarchal See, July 16/29, 1927. It was in vain that the faithful bishops, clergy, and laity implored Metropolitan Sergius to desist from playing the part of Judas but to take example from the Apostle Peter who wept bitterly over his sin, and to repent of his betrayal of Christ. But the admonitions did not help and the ecclesiastical schism of 1927 took place.

The Soviet authorities tried to arrest the confessors of truth in the Church. During the trials, the jubilant examining judges of the Tcheka proved the “strict canonicity” of Metropolitan Sergius and his Declaration “which compromised neither the canons nor the dogmas.”

The resistance of the confessors, the “Tikhonists” and the “Old-Churchmen” (who came to be called “Josephites”) was broken physically by the Soviet government with the aid of the Soviet church. The mass executions, persecutions, and tortures which shattered the Church which remained faithful to Christ baffle description.

According to the official figures of the Office of Scientific Research of Criminology in the Soviet Concentration Camps in 1929, the number of those sentenced for Church affairs amounted to 20% of all the prisoners in the camps. The true Russian Orthodox Church, faithful to Christ to the last, had no alternative but to withdraw into the catacombs.

The idea of the Underground Church was conceived by Patriarch Tikhon. He may be called the spiritual father of the Catacomb Church. In the first years of her existence, the Catacomb Church had no organization or administration. It was physically and geographically disconnected and was held together only by the name of Metropolitan Peter. Later, having had no contact with Metropolitan Peter for a long time, Metropolitan Cyril was acknowledged by the Catacomb Church as her spiritual leader and head.

In 1936, after the death of Metropolitan Peter and Metropolitan Cyril, Metropolitan Joseph became the spiritual and administrative head of the Catacomb Church which by that time had acquired some kind of organization.

Toward the end of 1938 Metropolitan Joseph was executed for being the head and leader of the Secret Catacomb. Church. After his death, the Catacomb Church kept her secrets more strictly, especially the names and whereabouts of her spiritual leaders. Information about the Catacomb Church was not easily come by. And as the enemies of the Underground Church, the soviet and pro-soviet churchmen, require but cannot obtain precise information as to the names, addresses, and activities of the members of the Catacomb Church, they deny its existence and call it a myth. If there exists a “Christ Myth” by Professor A. Drews, why should there not be a “Myth of the Catacomb Church?”

I had the good fortune and joy of being a member of the Catacomb Church from 1927 till 1944. While I was a convict in the Solovetsky Concentration Camp (1928-32), I attended many secret consecrations performed by Bishops Maxim, Victor, Hilarion (the Suffragan Bishop of Smolensk), and Nectarius. Similar secret consecrations of bishops took place also in other Concentration Camps such as Svirlag, Belbaltlag, and camps in Siberia.

From 1945 till 1949 news of the Catacomb Church behind the Iron Curtain was scarce and hard to secure, but it trickled through every year, including 1949. This information was, of course, smuggled out in extremely cryptic code.

“I will not tell the secret to Thy enemies” – under this motto on both sides of the Iron Curtain I received news of the Catacomb Church. I have had occasion to speak with refugees from “there” and of receiving letters from all parts of the world from former members of the Catacomb Church now scattered in exile. They were often complete strangers to me. They wrote to me on account of my articles, mostly in the periodical “Orthodox Russia.” Most of the letters were anonymous.

According to information in my possession received from an unquestionably reliable source, the Underground or Catacomb Church in Soviet Russia underwent her hardest trials after February 4th, 1945, i. e. after the enthronement of the Soviet Patriarch Alexis. Those who did not recognize him were sentenced to new terms of punishment and were sometimes shot. Those who did recognize him and gave their signature to that effect were often liberated before their terms expired and received appointments.

We have information that a priest after such a registration, told his wife and two daughters who had come to visit him that they should stop going to the Soviet Patriarchal Church when they returned home. “It is better not to go to any church whatever or receive communion at all than to be implicated in a church of evil-doers,” he said. The widow of the priest (he was shot after their visit) and her two daughters were persecuted by the Soviet priests who called them “schismatics” and “sectarians.” They were nourished in the Catacomb Church and kept the Sacrament in their house (1945).

“The persecutions of the secret priests and bishops were so cruel,” writes one-anonymous correspondent, a refugee from the Soviet Union, “that it was very difficult to find the secret Church.” The names of the bishops and priests of the Catacomb Church are kept in the strictest and most reverent secrecy. It is impossible to say with any accuracy how many there are, although information regarding the activity of more than ten secret bishops has even penetrated the Iron Curtain. Some of the secret bishops are now abroad. There are also metropolitans in the Catacomb Church. If it is not possible to ascertain the number of the priests (who are mostly secret hieromonks), we can say that it is known only that there are all too few of them to feed the flock that desires the ministry of such shepherds in the Soviet Union. Those hungry souls are “as the sand of the sea,” to quote a secret bishop.

The very existence of the Catacomb Church in the conditions of the Soviet Union would be impossible were it not that nation-wide thirst for the true, as distinct from a false, Church. The lack of priests is partly compensated for by numbers of secret nuns and also dedicated men and women who serve the Secret Church. They read Akathists and conduct group prayers of a general nature called “meetings by candle-light.” Some secret bishops call these pious people, who selflessly serve the Secret Church everywhere, “sub-pastors.” The sub-pastors mostly keep in their houses the Holy Sacrament which is obtained with great difficulty and the utmost caution on the rare occasions when meetings with the secret shepherds occur.

According to information given by later refugees (1947-1948), the work of the secret priests prior to 1948 (before the new registration of the clergy) was distinctly easier in the concentration camps than in “freedom.” But after 1945 it became more difficult inside the concentration camps than outside them. According to a secret priest from Siberia and a secret monk from the North of Russia who fled from the Soviet inferno in 1945 and whom I saw personally, there were occasions when “komsomols” of the “godless’ section who were known for their anti-Church activity were sent in obedience to party discipline as students to the re-opened Theological Seminary.

Citizens of Soviet Russia who formerly used to go to church nd then stopped going were sometimes summoned to the M.G.B. (former G.P.U.) and asked why they had given up going to church. They were forced to choose between going to the official church again or writing and publishing in a Soviet paper a complete repudiation of all religion as an “opiate of the people.” Thus, going to a Soviet church was tantamount to renouncing Christ and to the total rejection of religion. A priest of the Soviet church, who in 1948 left the Soviet Zone of Germany for the American Zone, told me personally how he had been summoned to the M.G.B. (G.P.U.) where he was “requested” so to influence an aged woman, mother of a Soviet general, that she would stop going to church. The priest, under threat of punishment, was forbidden to mention that the M.G.B. had been involved in the affair. He carried out the request.

All secret priests detected in the Soviet Zone of Germany have been shot. All priests who did not recognize Patriarch Alexis were also shot. According to the testimony of numerous refugees from Soviet Russia who attended Soviet churches in the years 1945- 1949, the majority of the believers are sharply opposed to the official church hierarchy and in particular to Patriarch Alexis personally. “I cannot live without church,” some people say, “but I do not recognize the Soviet Patriarch.” Many are going to the Soviet churches only because of the venerated and miraculous icons that are still there. “We go to church when there is no service to kiss the icons,” say others. “I go to church but I do not confess or communicate, because the bishops and priests are serving the Soviet government,” say others.

There are priests who at home weep and regret that they are serving in the Soviet church. But there are other priests and monks who say, “Now you can save yourself in the church by lying,” but “the keeping of the canons” is the most important thing. There are very few who approve fully of all that Patriarch Alexis says and does. The majority of those who do so are the intellectuals, professors who have adapted themselves to the Soviet regime. The simpler the people, the clearer they see the falsity in the church and deplore it. It is beyond doubt that the majority of the clergy and laity in the Soviet church are the so-called “apostates in time of persecution.” A refugee from “there,” a man devoted to the Church, who had sometime attended Soviet churches and who afterwards suffered on that account, asserts categorically, “If Russia is liberated and the Church calls people to repent for attending Soviet churches, the repentance will be sincere and nation-wide.”

The majority of those who go to the Soviet churches are convinced that abroad is “The True Russian Orthodox Church which does not acknowledge the Soviet Patriarch” (according to many witnesses). The name of Metropolitan Anastassy and his work are better known at the present time among the faithful in Soviet Russia than formerly the name and activity abroad of Metropolitan Antony. (For instance, almost no one knew anything of the Council of Karlovtsy). This great publicity is explained by the temporary German occupation when large numbers of Soviet citizens learned of the activity of the clergy abroad. During the first years of the occupation, the former Soviet citizens were unable to distinguish between the different jurisdictions of the Orthodox Church abroad and regarded them as all equal. But they gradually began to see the difference and then they greeted with deep joy the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia led by Metropolitan Anastassy, whereas they began speaking with indignation of the other jurisdictions. That explains why the majority of the so-called new emigration have become active members of the Church Abroad.

The exarch of the Baltic, Metropolitan Sergius (Voskresensky), who during the German occupation, extended his church authority to the districts of Pskow and Novgorod, strove in vain (threatening to suspend his priests) against the non-observance of his orders to remember by name in the church services the Soviet Metropolitan Sergius.

The priests of the Catacomb Church who began to serve in the Orthodox churches which were re-opened in large numbers by the Germans firmly refused to mention the Soviet metropolitan. For instance, in the town of Soltsy, in the diocese of Novgorod, Father V., formerly provost of the city of Minsk, refused to mention the Soviet Metropolitan Sergius notwithstanding the strictest orders of the provost of the Novgorod district, Father Vassily Rushanov. That was in 1942, but later Father V. became a catacomb priest and in 1943 he began secretly to remember Metropolitan Anastassy. Now it is well known that many of those who after the German occupation returned to Soviet Russia when attending Soviet churches secretly pray for Metropolitan Anastassy and regard him as Head of the Orthodox Church.

This is information, poor in quantity but significant in quality, which I obtained partly orally and directly, partly through correspondence with refugees unknown to me personally who came from behind the iron curtain between 1945 and 1949. While rejecting categorically the top prelates (the Patriarchs Sergius and Alexis and their active and convinced assistants), who have sinned against the Orthodox Church and the Russian people, we must be very cautious and attentive in deciding what is the character of their flock.

The Catacomb Church that exists today in the Soviet hell is doing a truly holy work. All persons who take part in that radiant Church, whether as archpastor, pastor, sub-pastor or simple members of the flock who join it deliberately and consciously, can be only a few, select souls capable not only of “living in the Church” (to use Khomiakov’s words) but also of dying a martyr’s death for her. Such heroism cannot be expected of the broad masses of the people. The masses have proved to be “the fallen in time of persecution.” The degree, forms, conditions, character, and circumstances of the fall must be taken into account in each individual case. The sin of apostasy must be denounced, but a distinction must be made in degree of responsibility in the case of the tempters, the tempted and those “little ones” who succumb to temptation.