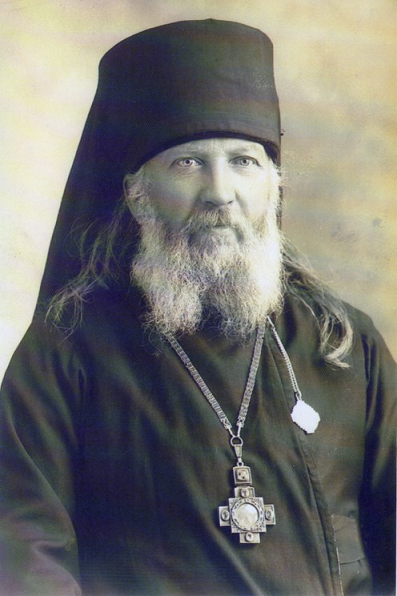

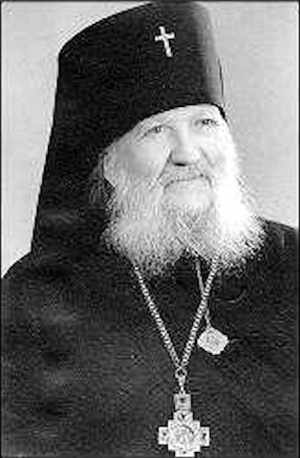

Archbishop Ioasaph Skorodumov of Buenos Aires Argentina Paraguay by Michael Woerl

Biography of Vladika Ioasaph (Ivan Vassilievich Skorodumov), Archbishop of Buenos Aires, Argentina and Paraguay

Archbishop Ioasaph was born on 14/26 January 1888 in the village of Rebovichi, Tikhvin county, Novgorod province (NW Russia, approximately 200 km. east of Saint Petersburg) of the Russian Empire. His birth took place three hours after that of his twin sister; they were “children of the fields and forests,” and at Baptism “were given the names of wildflowers, Ivan and Maria.” The twins had two brothers, one three years older, who was killed in the siege of Leningrad by the Nazis in 1942, and the other two years younger, who died at age 12. Maria survived into at least the late 1950s, and lived in Leningrad. [1]

Around the time of the birth of the future Archbishop Ioasaph, the Novgorod province had a population of 1,337,113; there were 1,182 churches, 24 monasteries and 12 convents with 1,053 monastics, 500 students attending seminary, and 51,700 children in school, 8,800 of which went to parish schools. 96% of the population of the province belonged to the Russian Orthodox Church. 81.6% of the population of the Russian Empire at the time was peasants-amounting to the staggering figure of 88 million. Merchants and “bourgeoisie” represented 9.3%, the military 6.1%, nobility 0.6%, and the clergy 0.1%. [2, 3]

Ivan’s father, Vasily Skorodumov, was priest of the village parish, and his mother was Feodosia Skorodumov, nee Kachalova. Feodosia Skorodumov died when the twins were just five years old; eventually most of the family business, work, and cares fell on Maria, who became the “little mother.” The family eked out a modest life in the Novgorod province-although cold and damp, the forests, lakes, and rivers that predominated in the province were beautiful and brought joy in the Lord’s creation. They were blessed to have a happy and loving family life, and little Vanya was a favorite, obedient and helpful. The children enjoyed friendship and camaraderie among themselves, and tried to go to every church service with their father, who they adored, and help him with small tasks at church. In their free time, the children hunted mushrooms and berries, and went fishing. Carrying heavy loads of fish the three or four mile walk back home, the boys would compete, trying to bear the load on the same shoulder the entire way. The string binding the fish would leave a deep blue-red bruise, nearly cutting into their flesh, which would frighten their sister, while their father only remarked, “You fools!” The boys, already acquainted with Lives of Saints, tales of local monastics, ascetics, and hermits, called their feat of endurance a “podvig.” [4]

When “little Ivan” was ten years of age, his father took him to Tikhvin, where he attended a school that prepared students for seminary. The priest’s son passed the entrance exam with flying colors. During his time at school in Tikhvin, Ivan Skorodumov undoubtedly visited the Tikhvin Dormition Monastery, founded in 1560 by an ukaz of Tsar Ivan Grozny (“the Terrible”). A visit to the monastery to venerate the wonderworking Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God, one of the most famous in Russian history, would have been a school “field trip.” The Wonderworking Tikhvin Icon, attributed to the Holy Apostle and Evangelist Luke, appeared miraculously in Russia, and was witnessed in seven different locations in the Novgorod Province until it came to rest on the banks of the Tikhvin River. Three wooden churches built to shelter the Holy Icon burned completely, but the Icon was not harmed. The stone Cathedral of the Dormition was built from 1507-1515 by the Grand Duke Vasily Ioannovich; the monastery grew up around it, in the very place the Mother of God chose to rest on the banks of the Tikhvin River. A pious youth, “little Ivan” could not but be moved by the spiritual beauty and atmosphere of the monastery, and the holiness of the Wonderworking Tikhvin Icon. Ivan Skorodumov graduated from the Tikhvin Spiritual School in 1902, with high marks, having earned a place in the Novgorod Theological Seminary [5, 6]

From 1902 to 1908, Ivan Skorodumov attended the Novgorod Theological Seminary, founded in 1740 on the basis of an ukaz of the Empress Anna Ioannovna. The Seminary was on the grounds of the Monastery of Saint Anthony the Roman, Wonderworker of Novgorod (“Antoniev Monastery”). During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Novgorod Seminary was a center of cultural life in Novgorod and Northwest Russia. Despite the close link with monastic life and the cultural activities, Seminary life in prerevolutionary Russia was both demanding and strict. The system of education was built on fear of punishment; violations of the harsh disciplinary code could result in whippings (with actual whips) and restraint in leg shackles. Antiquated regulations and maltreatment of students eventually gave way to more enlightened procedures. Saint Tikhon of Zadonsk and Stefan Lagovsky, later Archbishop of Ryazan and author of theological treatises, were among the most famous graduates. On the Seminary’s 150th anniversary, a new building on the Volkhov River, including large classrooms, facilities for the teaching and serving staff, a hospital with pharmacy, locksmiths workshop, a public school with classes taught by seminarians, a collection of local ecclesiastical antiquities, and a library which included the unique book collection of Archbishop Feofan (Prokopovich, 1681-1736) of Novgorod. As Archbishop Feofan was educated in Kiev, Poland, and Rome at the Papal College of Propaganda, it must have indeed been a unique book collection. [7-11]

The revolutionary activities of 1905 attracted even Seminary students. Vladika Ioasaph later told a story about a day that some of the students decided to go “on strike,” and not attend classes. As Vladika stated, “I always went to classes.” Several of the striking students blocked his way, and told him “Today is labor day-join us, don’t go to class.” He responded, “Labor day you say? Then I’m going to work!” As the strikers blocked his way, the future Archbishop pushed up his sleeves, and told them: “Get out of the way!” When they didn’t move, he asked, “Alright, who’s first?” “Seeing that I wasn’t joking, and knowing my physical strength, they decided to let me pass.” When he got to class, the instructor asked, “So, you’re not one of the strikers? Where are those rams?” The future Archbishop answered, “I am not the shepherd of the sheep.” The instructor told him to read the prayer, he read it, finished the exercise, and went to his room. The next morning, the “strike” was over. Ivan Skorodumov graduated from the Novgorod Theological Seminary in 1908, with high grades, and a glowing recommendation from his instructors. After successfully completing the competitive entrance examinations, he was accepted into the Saint Petersburg Theological Academy. His father had to be thankful to God, as well as delighted at the successes of his “little Vanya.” [12]

The Saint Petersburg Theological Academy dates its founding to 1721, and went through various permutations until assuming the form which was well known in 19th and early 20th century Russia-the premier educational institution of the Russian Orthodox Church. From 1913-1917, the name was changed to the Saint Petersburg Imperial Theological Academy. Along with the Academy were the Saint Petersburg Theological Seminary, and a Seminary preparatory school. The Academy also engaged in translation work-the Scriptures, Church Fathers, Byzantine historians, and ancient liturgies of east and west. Saint Feofan the Recluse, Saint Filaret (Drozdov), Metropolitan of Moscow, Metropolitan Antony (Vadkovsky) of Saint Petersburg, and Archbishop Feofan (Bystrov, then Archimandrite) were among the notable rectors of the Academy. [13]

The life of the capital-so different from the provinces, with a thousand novelties and distractions, did not interest Ivan Skorodumov. His interests were his theological studies, and church life. His “hobby” was his spiritual education. He was an extremely talented student, intelligence seeming to be a family trait. A “family legend” noted that their surname, “Skorodumov,” (which means “quick thinker,” or “quick witted” in English) was bestowed upon one of his ancestors for his correctly answered and quickly finished entrance examination to a seminary preparatory school. Ivan Skorodumov, Academy student, took keen interest in all his studies, but had a special love for the writings of the Holy Fathers, most especially Saint John Chrysostom. He also admired the rector of the Academy, Bishop Feofan (Vassily Dimitrievich Bystrov, 1872-1940, later Abp of Poltava & Pereyaslavl) of Yamburg, so much that he unconsciously began to imitate his mannerisms. This admiration would last a lifetime, leading to Bishop Feofan becoming his spiritual father, his abba, whose influence on the future Archbishop Ioasaph cannot be entirely understood by those of lesser spiritual understanding. [14]

Archbishop Feodosy (Pavel Ivanovich Samoilovich, 1884-1968) of Sao Paulo & Brazil attended the Saint Petersburg Theological Academy at the same time as Ivan Skorodumov. Vladika Feodosy remembered Ivan Skorodumov as being a year below him, not acquainted with him, but very much aware of him. He also remembered that Ivan was “strongly influenced” by Bishop Feofan (Bystrov), and under the academic guidance of Hieromonk Veniamin (Ivan Afanasievich Fedchenko, 1880-1961; Church Abroad until 1927; Constantinople until 1930, when he joined MP. Later Metropolitan of Saratov & Volynsk, reposed in Pskov Caves Monastery), who he worked closely with. In his last year at the Academy, he delivered his thesis, “Saint John Chrysostom on Monasticism,” and was granted a diploma of the first degree in Theology. The considerable amount of time he spent with Bishop Feofan (Bystrov), who was becoming well known in the capital, charted Ivan Skorodumov’s future path. [15, 16]

After his graduation, in the autumn of 1912, there was only one place Ivan Skorodumov wanted to go-to Astrakhan, an exotic city far from the Russian north, with a warm climate, and an oriental atmosphere. Where the Volga flows into the Caspian . . . He did not, however, want to go for the climate or atmosphere. Bishop Feofan (Bystrov) had been transferred to Astrakhan from European Russia earlier that year, primarily due to his insistence that Rasputin should no longer be allowed access to the Royal Family (Bishop Feofan had been confessor to the Tsarina Alexandra in Saint Petersburg). A steamboat trip down the Volga to Astrakhan was beyond his means, but he received the ticket as a gift. The night before the steamboat docked in Astrakhan, Ivan Skorodumov noticed he had only a few kopecks left. His sleep that night was fitful, and he dreamed of being broke and bleeding in Astrakhan, and a long ride to the Episcopal Residence, where he walked through long, dark corridors. When the boat docked, he rode the same roads, and walked the same corridors he had seen in his dream. On November 13/26 1912, Ivan Skorodumov was tonsured a monk on the feast day of his beloved Saint John Chrysostom. He was named for the newly glorified (1911) Saint Ioasaph of Belgorod. He regarded his tonsure as “a memory of heaven.” He was, of course, tonsured by Bishop Feofan, who also ordained the future Vladika Ioasaph as hierodeacon on 18 Nov/01 Dec 1912, and three days later, as hieromonk. The Training Committee of the Holy Synod soon thereafter appointed Hieromonk Ioasaph as Assistant Inspector of the seminary preparatory school in Yaransk, Viatka province (Northern Russia). And on 17/30 December 1913, he was appointed to the same position in Poltava (Ukraine)-where Bishop Feofan had been appointed the past March. Vladika Feofan suffered from poor health, and the strong, athletic Hieromonk Ioasaph was always near, assisting the frail Bishop, and faithfully serving him in everything. The Revolution caught both Vladika Feofan and Hieromonk Ioasaph in Poltava. Living in the seminary preparatory school hospital, Hieromonk Ioasaph and Viktor Konovalov (later Archimandrite Amvrossy) noticed the Bolsheviks surrounding the building. The bolsheviks occupied the building; the two would pass them in the halls, were never spoken to, or, so it seemed, even seen by them. The monks eventually moved to different premises. Bishop Feofan had a similar experience-when the Bolsheviks came to arrest him in his office, they entered the room. Vladika Feofan was sitting at his desk, and they looked around the office, appeared not to see him, and departed. [17, 18]

Hieromonk Ioasaph was elevated to Archimandrite in May 1920 in the Crimea, where he had travelled with the change of front lines between the White Army and the Red Army. Archimandrite Ioasaph lived in the Grigoriev Bizyukov Monastery in Kherson until the evacuation. The Monastery had been attacked, plundered, and some of the monks had suffered martyrdom in the confusing and chaotic situation which saw fighting in the area involving troops of the Reds, Greens (anarchists under Nestor Makhno), Ukrainian Hetmanate, Ukrainian Directory, and White Army. The situation returned to a semblance of normalcy after General Denikin’s White Army gained control there in early 1920. Archimandrite Ioasaph’s academic mentor from the Theological Academy, Hieromonk Veniamin (Fedchenko), with Denikin’s Army, was then Bishop of the White Army & Navy. He assigned Archimandrite Ioasaph as a preacher to the troops, and the strong voice of the Archimandrite could be clearly heard all the way in the last rows of the assembled soldiers. At the time of the evacuation, Archimandrite Ioasaph boarded the boat with eight Bishops. One of the Bishops left several pieces of luggage on the dock; minutes before the vessel embarked, Archimandrite Ioasaph ran down the gangplank, and grabbed them quickly-two strapped on each shoulder, two in each hand, and raced back on board the vessel just in time. The Bishop asked, “has the luggage been loaded?” “Yes.” “Was it labeled?” “Yes.” “Who helped you?” “God helped.” The Bishop, astonished, threw his hands in the air . . . A sad and sorrowful day, an exodus from Russia, sailing off into the unknown . . . [19, 20]

The exodus from Russia led first to Constantinople. From Dec 1920 to Feb 1921, Archimandrite Ioasaph was assigned by Bishop Veniamin (Fedchenko) to the Russian Military Hospitals in Constantinople. He lived together with Archimandrites Feodosy (Samoilovich) and Simon, as at the Grigoriev Bizyukov Monastery. They shared quarters in Russian Army Hostel Number Eight, where the assistant commandant was Viktor Konovalov. The short stay in Constantinople ended in departure for The Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, as Yugoslavia was officially known from 1918-1929. [21, 22]

Upon arrival in Serbia, the three Archimandrites were given the 14th century Serbian Monastery of Vratna as their living quarters. They served a nearby village where the inhabitants spoke Romanian, a parish sixteen kilometers from the village, and their own services in the Monastery. The only other inhabitants in the monastery were the watchman and his family. They lived separately, as two different families, each preparing their own food, eating together, and taking care of their own duties. This arrangement did not last long. Archimandrite Ioasaph went to Erceg Novi in Dalmatia with his abba, Archbishop Feofan. In Erceg Novi, (Montenegro), Archimandrite Ioasaph taught and served as priest of the Russian Grammar School, founded by evacuees from Russia like himself. The situation was described in a letter written by a teacher at this same school: “After the dark, dirty confined quarters of a ship, we thought Erceg Novi was a paradise! Palm, lemon, and orange trees, roses everywhere, the people were friendly. Our first concern was that our children learn Russian. Poor in means, but rich in hope, we started a school. Shortly after we started the school, our priest left us-he was sent elsewhere. But God did not leave us-soon after, Archbishop Feofan and Archimandrite Ioasaph came to us. Our school grew, and our Russian community became a little town itself . . . we were all poor, and our priest, Father Ioasaph, we thought, was just like us. We soon found that he was more impoverished than us all . . . he was one of those iconic individuals, well-liked by all, a person whose rare blue eyes shone with the blue light of evening, tenderness, and peace and quiet. ” This, too, was a short lived arrangement, and Archimandrite Ioasaph was again given a different assignment. [23, 24]

The new assignment for Archimandrite Ioasaph was at the Don Cossack Cadet Corps of the Emperor Alexander III, in Gorazhde (now located in Bosnia). The Cadet Corps was a hallowed Russian institution, in many ways equivalent to the “Military School” familiar in the West. There were several different Cadet Corps in Russian history, organized and supported by different Russian Army Divisions to train future officers. The students of each Cadet Corps were required to join the Army Division that was the patron of the school they attended. In prerevolutionary Russia, army enlistment meant a twenty-five year commitment. In the emigration after the fall of Russia to the Bolsheviks, the reason for the existence of the Cadet Corps was transformed-it would become a means for the salvation of Russia. The Cadet Corps would train a nucleus of military personnel who would lead a crusade to take Russia back from the Bolsheviks, and return it to its proper heritage. During the phase of the emigration prior to World War II, saving Russia was seen as a possibly imminent event that. After the evacuation from Russia, the Don Cadet Corps relocated several times-Turkey, Egypt, different locations in Yugoslavia, until, in 1926, the Corps relocated to Gorazhde in Bosnia. They were given use of a former Austro-Hungarian military camp, consisting of several buildings that could be used as a church, classrooms, barracks, kitchens, etc. The Corps was occupied this facility until it was disbanded in 1933. [25 – 28]

A former cadet under the tutelage of Archimandrite Ioasaph told of his paternal care and love for the cadets, who felt lonely and abandoned. This paternal love could be gentle, and almost motherly, but also monastic and somewhat harsh. This helped the cadets to “build armor between themselves and the world.” But “as snow would melt from the sun,” all hurt and bad feelings would “melt from his smile.” The cadets considered that the fundamental quality possessed by Archimandrite Ioasaph was kindness. He had replaced Bishop Veniamin (Fedchenko, who went to Paris) at the Cadet Corps. There was a small monastery attached to the Cadet Corps, which provided clergy for the services attended by students. After lunch and before evening classes, Vespers and Matins were served. The future Archbishop gathered around him the Cadet “Churchmen,” that is, those cadets who served in the altar and otherwise assisted at the Services. He discussed at length everything to do with their duties, and was very concerned with teaching them to ring the bells properly. Although in the emigration, “due to poverty, bells were replaced by oxygen cylinders and rails,” they were taught to produce “melodious chimes.” The cadets were amazed at the strictness of Archimandrite Ioasaph’s monastic life-he absolutely refused to own any property whatsoever; his cell was the “property” of all, they could enter at any time, whether he was reading or asleep in his podriasnik. It was always neat, and devoid of “decoration,” only icons on the wall, and a lampada. The bed was hard and narrow. In the winter it was cold in the cell, which was only “slightly heated.” He held lengthy discussions with the senior cadets, and would stop by the younger cadets dormitory, and read to them from the Lives of the Saints. On occasion, Father Ioasaph would go fishing in the nearby Drina River, or walk up into the mountains or along the river to enjoy God’s creation. When returning from fishing, he would always give away his catch. There were cadets who considered Father Ioasaph as their “personal educational institution.” These were the “Churchmen,” who Father Ioasaph would take on two or three day excursions to local monasteries, parishes, and other points of interest. They had to travel by foot, and learned much from simple conversation with Father Ioasaph along the way. The author of the cadet memories remembered this time fondly for the rest of his life. Years and years later, when recalling these times, he could “see” the Father Ioasaph of his most beloved memories, a bright smile on his face, blue eyes shining, the breeze blowing through his hair, gazing at mountains, forest, river, and exclaiming, “How wondrous are Thy works, O Lord! In wisdom hast Thou made them all!” (Psalm 104) Although many attempt to proclaim their love and concern for young people for ulterior motives, even good ulterior motives, young people have an uncanny knack of knowing who is genuinely concerned for them, and who is not. Archimandrite Ioasaph’s success with the students at the Cadet Corps was absolutely based on the fact that he was genuine. The cadets knew his love, concern, care and friendship for them was genuine; they knew his monastic life was genuine, they knew his love for God and His Holy Church was genuine. Precisely because of this quality of genuineness, Father Ioasaph was able to truly reach his students, and his influence on them was something that lasted a lifetime. [29]

Professor M. Khrisanogov was one of Vladika Ioasaph’s lifelong friends. The professor was an artist, and instructed Archimandrite Ioasaph in drawing and painting during the period at the Cadet Corps. The friends often had long discussions-while walking in the mountains, looking for the “right spot” to set up their easels and paint, while painting, and every time they had an opportunity. While their discussions included a wide variety of topics, the professor felt the friendship lasted for so long because it was based on discussions about faith in God, the miracles of God, and how God chooses those He wants to serve His Church, or help through miracles, and the role of prayer in these miracles. One time, they came across a Muslim woman exhausted and sick on a stretcher, near a “temple.” Father Ioasaph approached the woman, and asked if she believed in Christ and prayer. The woman replied that she did believe in “the Lord and prayer.” As soon as the words were uttered, she got up from the stretcher, and returned to her home unaccompanied, with no help. Father Ioasaph, because of his humility and meekness, did not want such events to be made known, and the professor had seen others. He never mentioned them to anyone, until several years later, when he was in Sremtsy Karlovtsy, painting a portrait of Metropolitan Antony (Khrapovitsky), with then Bishop Ioasaph also present. The painter was recalling several incidents where the prayers of Father Ioasaph had resulted in relief for the suffering. Vladika Metropolitan Antony, in tears, exclaimed: “There are believers in this world!” Bishop Ioasaph and his friend, both deeply affected by the tender feeling of Vladika Metropolitan Antony, themselves started shedding tears . . . [30]

In 1929, Viktor Konvalov, now living in Canada, wrote to his friend Archimandrite Ioasaph, that, “due to the schism of Metropolitan Platon, there were no legitimate Orthodox clergy in Canada,” but the land was reminiscent of Russia, and fertile ground for the planting of the seed of the word of God. He concluded by asking, “do you want to come?” His answer was , “I do!” The same year, a “soborno-thinking” group of people in Montreal, decided to open a new parish, and also asked Archimandrite Ioasaph to come to Canada and serve as rector of the new parish. This invitation was made with the consent of Archbishop Apollinary (Andrei Vasilievich Koshevoi, 1874-1933), who ruled the North American Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia at the time. After arriving in Montreal, due to difficulties with his documents, he had to leave Canada and return to New York. After two months in New York, in Feb 1930, he was able to return to Canada with a two year visa. Archimandrite Ioasaph was appointed as Bishop of Montreal, Vicar to the North American Diocese, on 29 April/11 June 1930. In Sep 1930, he was summoned by the Synod to return to Yugoslavia for his consecration to the Episcopate. [31, 32]

The nomination service took place on Saturday, 28 Sep/11 Oct 1930 during a five hour Vigil in the Holy Trinity Church (built by donations of Russian emigres, main Church of the ROCOR in Serbia) in Belgrade. A “huge gathering of clergy and laity” was present, presided over by Metropolitan Antony (Alexei Pavlovich Khrapovitsky, 1863-1936), with Archbishop Germogen (Grigorii Ivanovich Maximov, 1861-1945) and Bishop Mitrofan (Abramov, 1876-1945) concelebrating. With singular expressiveness, Bishop Ioasaph read the Confession of Faith, and the Oath to the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. The consecration took place the next day in the “Big Cathedral” (probably the Cathedral of Saint Mark of the Serbian Church, which is nearby the Holy Trinity Church). Many monastic clergy, friends of the new Bishop were present. During the Liturgy, after the consecration, Bishop Ioasaph performed his first ordination-he ordained the Hierodeacon Sava (Konstantin Petrovich Struve, 1903-1948) to the priesthood. When presenting the new Bishop to the faithful, Metropolitan Antony spoke heartfelt and edifying words about the struggles faced by the new Bishop in America, and of the extraordinary personal qualities of the new Bishop. Metropolitan Antony told him, as he handed him his Bishop’s staff, “You are going to people who have long lived with an understanding of things that has nothing whatsoever to do with Christianity. Bring them the teaching of humility; accept this staff as a staff of benevolence and, as you bless the people who now stand before you, think of the flock there, who already love you.” The Liturgy was characterized by a solemn and prayerful mood, a testament to the high regard in which Bishop Ioasaph was held. In his speech at the nomination, Bishop Ioasaph spoke on the two questions that had directed his life-the first was the study of the grace of God-he said that life had taught him that the grace of God towards mankind was limitless. The second concerned whether the Dread Judgment would come soon, and after looking at the condition of people, and himself, he decided that it would. He came to the conclusion that it was the limitless mercy of God that brought him to Episcopal service, and that if God, in His mercy, could bring him, in that service, to save his soul, and the souls of the faithful, he could only accept with humility, and hurry to bring people to the Kingdom of God. He concluded with asking the prayers of all – “the Holy Hierarchs, the God loving clergy, and the pious lay people” – present. [33 – 36]

Shortly after his consecration, Bishop Ioasaph traveled to Montreal. About 100 people were at the dock to meet him, and they immediately went to the church, where he was greeted by the priest, Fr. A. Tsuglevich, and numerous parishioners. Viktor Konovalov, who had sold his house to pay Bishop Ioasaph’s fare from Yugoslavia to Montreal, recalled that Bishop Ioasaph came onto a “thorny path” with his arrival in Canada. There were numerous rival jurisdictions-the North American Metropolia, and several Ukrainian jurisdictions. Many in Canada, “even Bishops,” slandered Bishop Ioasaph, and attempted to prevent his work. The new vicariate had no assets and no organized parish life. Having come to Canada nearly penniless, Bishop Ioasaph had no salary but lived on donations. He was subjected to hardship and adversity. Everyone, it seemed, was worried-except Bishop Ioasaph. After ten years, there were 40 parishes, a Cathedral in Edmonton, a monastery, and the Holy Protection Skete, where Vladika Ioasaph’s friend, Viktor Konovalov became the abbot (Archimandrite Amvrossy). All was accomplished by small donations and hard labor. At the skete, Bishop Ioasaph labored, mightily-cut down trees, dug out stumps, cleared a space for the garden, planted and harvested the garden, cut wood for the winter, kept woodstoves going, no task was beneath him. He also labored in the construction of churches and other necessary facilities and painted icons for the churches. Someone once asked Vladika Ioasaph who had built the skete church-Vladika answered laughing, “There were four of us: Fr. Ilya, me, me, and Fr. Ilya.” [37 – 38]

In Vladika Ioasaph’s later years in Canada, he had about 60 parishes. He would visit these parishes as often as he could, and the parishes in which he was more comfortable, he sometimes came unannounced. Sometimes he would stay a week or so with an acquaintance. He was invited to a parish in Saskatchewan, and when he got off the train, knew the parish was about 40 miles away. He expected that someone would be there to meet him, but there was no one. He simply shouldered his bags and traveled the rest of the way on foot. Sometimes at the Skete, he had to light candles, light the charcoal for the censer, read the Hours, and intone all of the deacons litanies. Vladika Ioasaph was of the conviction that monks should never seek awards or elevations in status. When the Council of Bishops of the ROCOR elevated him to Archbishop on 16/29 October 1945, he remarked: “Why me? I should go to another jurisdiction!” Vladika Ioasaph had to endure the barbs of “ecclesiastical fighting” with the other “renegade” jurisdictions in Canada, and he always defended his flock, and the truth of the position of the ROCOR. One summer, there was a drought. Clergy of the American Metropolia led processions, blessed water, and went out to bless the fields. But-no rain. Bishop Ioasaph served a moleben, asking the Lord to bless the earth with rain. As the heavy rain poured, Vladika Ioasaph remarked, “Now you can see which side proclaims the truth!” Lest anyone have the wrong idea, the stories and anecdotes of Vladika Ioasaph were always in a humorous vein; he never told stories of conflict or unpleasant occurrences, as he simply did not wish to remember such. The aforementioned incident of the rain, Vladika attributed only to the faith and prayer of his flock. [39]

In 1935, in a meeting of the hierarchs of the Russian Church Jurisdictions in the emigration, called by Patriarch Varnava (Rosich) of Serbia, it was decided that the jurisdictions would unite under the ROCOR. This decision calmed jurisdictional troubles in Canada. This situation lasted in North America until 1946, when the North American Metropolia once again went on its own. Vladika Ioasaph was one of the Hierarchs who remained faithful to the ROCOR at this 1946 Cleveland Sobor. As a result, in 1947, the ROCOR divided its Canadian Diocese into two parts-Vladika Ioasaph continued his work in Edmonton, the western half, while the eastern half was assigned to Bishop Gregory (Georgi Ivanovich Borishkevich, 1889-1957), whose Cathedra was in Montreal. In Dec 1950, at a meeting of the Hierarchical Sobor of the ROCOR, a discussion was held concerning what approach, if any, should be used to attempt reconciliation with the North American Metropolia. Vladika Ioasaph was put on record as stating that, due to his long experience with the North American Metropolia in Canada, he “categorically opposed any conciliatory steps.” [40, 41]

The Hierarchical Sobor also heard Vladika Ioasaph’s report on the Western Canadian Diocese. After the report, it was agreed in the Sobor that Archbishop Ioasaph would continue as head of that Diocese, and that Bishop Leonty (Vasily Konstantinovich Filippovich, 1907-1971) would be sent to Canada as Vladika Ioasaph’s Vicar. Later at the Sobor, a report was heard on the Diocese of Argentina. The report came from a priest of the Diocese, and he noted that it was an urgent matter for the Sobor to appoint a ruling Bishop for Argentina. The first suggestions for the post were Archbishop Tikhon (Alexander Troitsky, 1883-1963) of Western America & San Francisco, and Archbishop Ieronim (Ivan Ivanovich Chernov, 1878-1957) of Detroit & Flint. Both declined on grounds of ill health. Metropolitan Anastassy (Alexander Alexeievich Gribanovsky, 1873-1965) then suggested Archbishop Ioasaph. Vladika Ioasaph, always the obedient monk, accepted without comment. It certainly must have been difficult for Vladika Ioasaph to leave Canada after nearly twenty years. He loved Canada for its climate, similar to the Russian north, where he was from. He had even taken up photography while in Canada, and took those photographs with him when he went to Argentina. The photos were described as a “fascinating visual document” of Vladika Ioasaph’s monastic exploits and labors, as well as scenes of Canadian nature. A number of the photos are described as “Vladika at work,” (obviously Vladika’s camera used by another) and show Vladika Ioasaph wielding an axe to cut down trees, clearing fields, working on buildings… [42, 43]

It seems that Vladika Ioasaph could have easily declined the appointment to Argentina for the same reason that the other two Bishops had declined-poor health. Shortly before the 1950 Sobor, he became gravely ill, and had to undergo a serious operation. Archbishop Ioasaph that arrived in Argentina during Great Lent of 1951 was not the same as he had been just a few years before. The official appointment of Vladika Ioasaph as ruling bishop of the Diocese of Buenos Aires & Argentina came on 10/23 July 1951. His new flock greeted him with great joy, and the first service was held in the Cathedral of the Resurrection, located at that time in a leased basement. Vladika Ioasaph referred to it as “the catacombs.” It was not long before the people of the diocese grew to love Vladika Ioasaph. His love for his flock, his sincere concern for the parishes, and for prayer, and his constant joyous countenance won their hearts. Under his guidance, construction of the Cathedral began in 1952, which was a joy to all. However, it seemed the old jurisdictional disputes had followed Archbishop Ioasaph from Canada to Argentina. His duties were not confined to disputes, disagreements, administrative work, orders and sanctions. He was not primarily an administrator, and always forgave his subordinates any offense. Some condemned him for this, and Vladika answered them, saying, “The police, among others, are employed to make sure orders are enforced; the Bishop only advises that it would be best to carry out an order.” It seemed that the heartfelt love and gentle treatments towards his flock was more effective than unrelenting strictness and imperious commands. Little by little, the life of the diocese was regularized: parish churches that had belonged to private persons and “brotherhoods” were property of the diocese as of June 1952, and in August 1953, the diocese was registered with the proper ministry, thus legalized in Argentina. Visitors would often find Vladika reading the Holy Fathers in his cell, which was, indeed, a monastic cell: a narrow, hard bed, an analoy with a prayerbook lying on it; a few icons, a lampada, and an epitrachelion hanging on a nail in the wall. Visitors would exclaim, “Vladika, Bless!” The door was always open, visitors could come to Vladika early or late, and they would always hear his welcoming response, “God Bless!” Anyone who visited experienced extraordinary peace, and tranquility of heart. Archimandrite Sava (Sarachevich,1902-1973, later Bishop of Edmonton) lived with Vladika Iosaph . Vladika loved children, and always had young people participate in reading, serving in the altar, singing in the choir-he knew from experience that childhood service in the church binds one to the Church for life. Vladika Ioasaph was a lover of books, and acquired a spiritual library rare for that time. Before his repose, Vladika willed his library to the Diocese. [44]

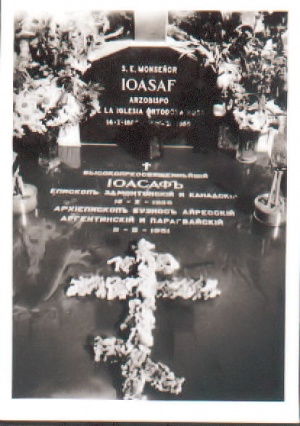

The hot, wet climate of Argentina was not healthy for Vladika Ioasaph. When other Bishops learned of the operation he had before leaving Canada, they were astounded. “Who? Vladika Ioasaph? It cannot be!” Vladika Ioasaph himself studied medical books after the operation, and learned he had cancer. He did not fall into despair, but accepted his illness with humility and obedience to God. His main “problem,” he felt, was not the disease, nor the suffering, but his inability to serve. His humor did not leave him, as he joked with his physicians in Argentina, “ the doctors in Canada said I had just two or three months more to live. I deceived them! I’ve lived several more years already!” After the second operation, Vladika recovered his energy. But in mid-March 1955,Vladika suffered a setback, and within one week was in critical condition. The news spread quickly, and at the Adoration of the Holy Cross, on a Saturday, the churches were filled with people offering prayers for the recovery of their Archpastor. “Rarely has such power of prayer reached the Lord!” By Pascha, Archbishop Ioasaph could serve. Although his doctors had forbade him to serve, he stayed for the Liturgy, which was special consolation for his flock. Many Russian s had settled in the village of La Bolsa, and it was Vladika Ioasaph’s dream to build a small monastic skete there, “for rest.” “Now, if God will only provide three bells to buy!” In June, Vladika suffered another setback. His beloved Abba, Archbishop Feofan, comforted him in a dream, and afterwards Vladika said it was easier for him to sleep. He would often say that “What is here is not important, our life on earth is nothing! If I could but see a little of heaven, I could die today!” At the time of Vladika’s suffering, his favorite subdeacon and other young people were “on duty” all night. Shortly before his death, Vladika Ioasaph could barely speak, but managed to say to visitors, “Christ save you all!” He reposed on 13/26 November, 1955, which was 43 years to the day after his monastic tonsure, on the feast of his beloved Saint John Chrysostom. All the local clergy served at his funeral, and the church was as filled as at Pascha. Vigil on Saturday, Sunday Liturgy, and the funeral for a Bishop were all served. The monastic burial service followed, and countless people came from all over Buenos Aires to say goodbye to their Archpastor, and kiss his mitre and right arm, his right hand holding the simple cross he was given at tonsure, his left, the Holy Gospels. Vladika Ioasaph was buried in the English cemetery in Buenos Aires. Memory Eternal! [45]

Long after Vladika Ioasaph’s repose, those who had known him often remembered the words of their Archpastor: “Do not judge. You don’t know, maybe God has already forgiven the one you have condemned.” [46]

Sources:

- Arkhiepiskop Ioasaf (I. V. Skorodumov) : v vospominanii︠a︡kh ego sovremennikov. No author mentioned. Buenos Aires, 1977 This book includes several sections; the section entitled Zhizhn Arkhipastiria was the primary source for this biography. It can be accessed online (Russian language only) at fatheralexander.org

- wiki.znanie.ru

- en.wikipedia.org

- op. cit. 1

- ru.wikipedia.org

- op. cit. 1

- drevo-info.ru

- ortho-rus.ru

- op. cit. 7

- op. cit. 5

- op. cit. 2

- op. cit. 1

- ibid.

- ibid.

- ibid.

- op. cit. 8

- op. cit. 1

- op. cit. 8

- op. cit. 1

- bizukov.or.ua

- op. cit. 1

- op. cit. 3

- op. cit. 1

- op. cit. 3

- op. cit. 1

- xx13.ru

- ruscadet.ru

- op. cit. 5

- op. cit. 1

- ibid.

- ibid.

- “Enlightener of Canada – Archbishop Ioasaph”

The Orthodox Word, Mar Apr 1968

online at roca.org

- Ibid.

- op. cit. 1

- pravenc.ru

- op. cit. 3

- op. cit. 1

- op. cit. 32

- op. cit. 1

- sinod.ruschurchabroad.org/documents.htm

- op. cit. 1

- op.cit. 40

- op. cit. 1

- ibid.

- ibid.

- ibid.

Photo sources:

- Abp Ioasaph – pravoslavie.ru

- Abp Ioasaph 2-roca.org

- Tikhvin Icon ru.wikipedia.org

- Tikhvin Monastery 1883 tihvinskii-monastyr.ru

- Tikhvin Mon. Royal Doors Tikhvin Icon on left tihvinskii-monastyr.ru

- Vratna Manastir today pravoslavlje.nl

- Novgorodskaya counties map uezd ru.wikipedia.org

- Novgorodsaj Gubernia map ru.wikipedia.org

- Cadet Corps church xx13.ru

- Cadets on inspection ruscadet. Ru

- Cadet buildings in Gorazhde st.jag.ru

- Antoniev Mon. location of Novogord Seminary ru.wikipedia.org

- Novgorod Seminary museum.novsu.ac.ru

- Archbishop Feofan (Bystrov) antimodern.wordpress.com

- Rebovichi location map countrysite.spb.ru